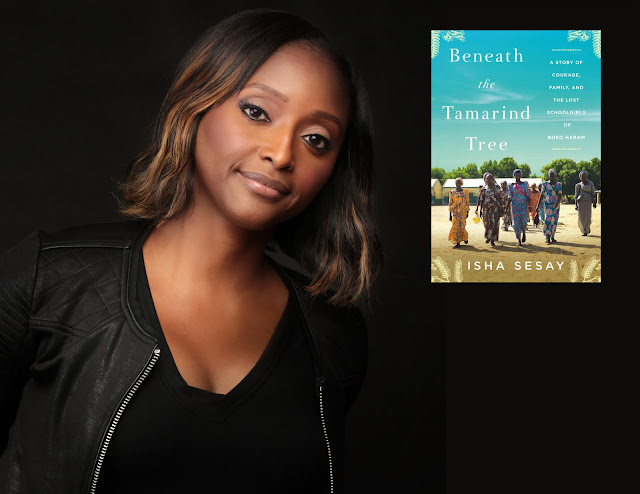

Here are a few excerpts from a book I recently read, "Beneath the Tamarind Tree A Story of Courage, Family, and the Lost Schoolgirls of Boko Haram," by Isha Sesay.

If not for fate, twinned with my mother’s childhood determination, I could just as easily have started off in a place not much different from Chibok and been one of the millions of girls facing countless obstacles to gain an education. Instead, my parents saw educating me as a priority, and I considered the freedom to dream up countless different paths to my future a birthright—all of which cemented the foundation for the life I have today. I am a living testament to the transformative power of education, and that truth never leaves me.

All the girls were crammed into the midsize hotel room, arrayed in brightly colored blouses, ankle-length skirts, and head wraps. The jam-packed room was a canvas of bold reds, blues, and yellows. My arrival didn’t interrupt their singing, though a few gave me small half smiles. Others looked as if they were far away, lost in reverie. I quickly realized they were singing Christian praise songs and many of them were holding Bibles: this was their daily evening worship—a time for exultation and prayer. Many of the girls sat on the bed, while others perched on the writing desk, and the remaining handful shared the few uncomfortable-looking chairs in the room. I spotted an unoccupied nightstand to the right of the bed and quickly made a beeline for it. From my corner, I found myself clapping along with the group while they sang. Though I quickly became swept up in the emotion of the room, I was struck by the serenity on the girls’ faces. There was no sign of pain, anger, fear, or dark emotion in their expressions. How were these girls able to manifest such peace and joyfulness after being held captive for more than two years, after witnessing the worst of humanity? I struggled to make sense of it. Yet here they were, twenty-one girls with their spirits seemingly untainted, creating a sound so beautiful my own heart was buoyed beside theirs.

Tim soon arrived with his camera and positioned himself in a corner by the door to unobtrusively capture the singing and clapping. At first I worried that the girls would find his presence upsetting, but they were so focused on their singing that they remained oblivious to him. The girls took turns leading the songs. One would sing a few lines unaccompanied before the rest swooped in to carry the remaining verses higher and louder. It seemed to me that they’d developed a way of supporting and encouraging each other that was palpable in their singing. I felt cocooned by their voices and could have stayed there for as long as they had the breath to sing.

But after half an hour, their voices trailed off and the girls reached for their Bibles, ready to begin studying. I motioned to Tim for us to leave. My departure, like my arrival, was barely acknowledged. With heads bowed, the girls were immersed.

I tried to tamp down my anxieties, reminding myself that there were no other journalists traveling back to Chibok with the girls. My journey would be a world exclusive, the kind of assignment that journalists live for. Turning back to look at the contents of my bag strewn across the bed, I noted that the question reverberating at the back of my mind was far simpler: But is it actually worth dying for?

As you read this, there may well be a part of you wondering why you should care about this story, about these twenty-one girls, after all this time. The world has moved on, you say. You’re probably thinking I should do the same.

But pause and listen to me, just for a moment: I’m not asking you to care about the girls simply out of tenderhearted humanitarianism. I am also asking you to care about these girls out of pure self-interest. If you view what happened to these girls through the lens of national security, you’ll see inherent in this tale the potential threat to you, your loved ones, and the global strategic interests of the United States.

We can ill afford to ignore the actions of any terror group simply because its concerns appear to be entirely local, or its murderous activities are taking place far away. Terrorism in the twenty-first century has no borders. So with that in mind, I’m urging you to remove the boundaries on your thinking. What happened that harrowing night in Chibok wasn’t just Boko Haram triggering a slow-moving nightmare for the people of that quiet community. It was also a flare illuminating the path of a transnational terror group with mutating ambitions.

One last thing: what happened in northeastern Nigeria in 2014 also offers a microcosm of the clash between opposing forces fighting to reshape our world. The mass abduction brought into focus a larger global narrative unfolding at this very moment. We are in the midst of an epic power struggle between militant Islam and the West, between progressivism and conservatism, between globalists and nativists, between a hoped-for open future benefitting many versus a set-in-stone, closed-off past rewarding the few. Boko Haram’s actions in Chibok spotlight the efforts of regressive forces to deny an education and autonomy to huge swathes of people in an attempt to keep them underfoot and make them easier to control. The education advocate and Nobel Prize winner Malala Yousafzai, herself a survivor of the Pakistani Taliban’s violent efforts to thwart her education, has repeatedly spoken of the fear felt by extremists, saying, “They are afraid of books and pens, the power of education frightens them. They are afraid of women, the power of the voice of women frightens them.”

As individuals and as a country, to know the intention of groups like Boko Haram and to still look away from the Chibok girls is to betray our shared humanity. The horrors that these girls have endured do not belong in a Nigerian vacuum. The place for every single one of them is right at the heart of the conversation about the global threats America is facing, and the development of a more holistic counterterrorism response that might just make all of us a little safer.

For Chibok’s Christians, devotion to the land is matched only by their passion for Jesus Christ; these are the twin tenets of life in this community. From birth to death, the focus is on God above and what comes from the earth beneath their feet. For these Christians, most of whom belong to the Church of the Brethren in Nigeria (Ekklesiyar Yan uwa a Nigeria, or EYN), faith isn’t a hidden-away, occasional pursuit; it is a fervent, communal, all-consuming affair, the center of which is daily worship. Every morning in almost every single Christian home in Chibok, the same ritual has played out for decades, adults and children rising from beds and mattresses, wiping sleep from their eyes, readying themselves to worship and praise the Lord.

The girls struggled with their choices. Should they flee into the night, uncertain of what may be lying in wait beyond the school walls? Or simply stay put, right where they were, with the risk of being trapped if Boko Haram burst into their school?

“Let’s pray, before we do anything,” Priscilla said. At her instruction, the dozens of girls, Christian and Muslim, sat together on the ground and drew close to form one group. They bowed their heads in desperate prayer. The chaos from the town was spreading. The praying girls could hear doors opening and closing all around them, followed by quickened footsteps.

As the entire family crowded around and cradled her in their arms, Saa felt as though she’d died and come back to life. The horrors of the night quickly receded, and soon there were no more thoughts. All that mattered were the surging feelings of love, joy, and gratitude that remained.

It seemed as if the entire population of Chibok town was there, packed into that schoolyard. As the minutes ticked by, the sense of mourning deepened. Soon the collective sorrow was so great, it was nearly impossible to distinguish the anguish of parents whose daughters had been taken from the misery of the rest of the supportive community. Distraught parents, distressed family members, concerned locals, all of them stood together weeping and shouting in mounting confusion and anger.

Meanwhile, the lack of visibility for the missing girls’ parents also factored into how everything played out. The president’s supporters routinely argued that the absence of TV and newspaper images featuring distraught Chibok parents was yet more proof that no girls had been taken. The truth was that the majority of the missing girls were from families so poor, they simply couldn’t afford to travel to places like Lagos and Abuja, where, at least for a time, hordes of journalists were eagerly waiting to hear their stories of what had happened on that hot night in April. These heartbroken parents were held back by not only their inability to afford the hefty transportation costs, but perhaps just as much by their limited education. Chibok isn’t some media-savvy community whose locals would grasp the critical importance of getting the stories of their missing daughters out to Nigeria and the wider world. As a result, there was a gap created by their lack of visibility and silence. Unfortunately, many inside and outside the government would step up to fill it with spin.

Mary was among the nearly one hundred girls who formed a convoy following on foot. She shuffled along while wearing just one blue-black flip-flop, urged forward by a phalanx of grim-faced men with their fingers resting on the triggers of long-barreled guns, which they seemed ready to use at a moment’s notice.

Sweat ran freely down her back as she tried to stay alert and avoid potholes that might send her tumbling. Mary walked with her mind wrapped up in thoughts of her parents, picturing them totally distraught at the news that their only child had been taken. She feared the loss would destroy them. Mixed in with that fear was a sense of foreboding that Mary couldn’t shake off, a distinct feeling that her life still hung in the balance. Every time this idea rose to the surface of her consciousness, it came with the question, What will I tell God if I am killed? She felt unprepared for death, uncertain she’d done enough in her short lifetime to give a successful accounting.

The next day, the captors arrived with a message: “We will kill you if we ever catch you performing Christians prayers again.” Priscilla believed every word of the threat. Petrified, they could no longer find it within themselves to gather in the dark in large groups, but they refused to abandon the practice altogether. They continued to look for opportunities to replenish their faith. When the moments presented themselves, Priscilla found they were almost always unannounced and involved no more than two to three girls. They weren’t regular occurrences, but these impromptu worship moments provided not only peace and succor to distressed souls, they also brought the spark that kept the spirit of defiance burning within the group.

After weeks of deprivation and suffering, the girls suddenly wanted to see what they looked like. With the sun high in the sky and a sense of curiosity burning within, Priscilla and Bernice among handfuls of other girls sidled over to an area not far from their rooms where Boko Haram had abandoned its broken-down motorbikes. The girls knew their captors were watching as they crowded around the bikes’ small rearview mirrors. They stared, wide eyed, at their own reflections, almost as if they didn’t recognize the faces staring back at them. When Priscilla finally looked in the mirror, she was shocked by how much she had changed. The girl in the mirror looked nothing like the girl who’d been at school in Chibok. From time to time a schoolmate would actually turn up with a broken-off rearview mirror hidden away in her hijab. In those squalid spaces where they lacked everything, the mirror became a prized possession, passed among the girls excitedly. Jida was all too aware of what was happening, but rather than confiscate the mirror, he would gently chide them. “Put it away,” he said whenever he spotted them gathered together and engrossed in their reflections. “It will only make you think more about what you have left behind,” the old man always added. But for the girls, staring at the round disk was more than a frivolous pastime—it was also a means of reconnecting with the girls they used to be, another lifetime ago.

Boko Haram’s unbending opposition to girls’ education is, in essence, an expression of its desire to silence them. To deny females a voice is to take away their ability to challenge the very practices and norms that subjugate and harm them. Successive Nigerian governments shaped a response to this tragedy that included minimizing and ignoring the voices of those fighting for the girls’ return. And with the international media attaching so little importance to the voices of Africans, news bosses easily moved on and global audiences tuned out.

All of this has driven me to use my own voice to keep this story on people’s minds. I also understand that the only reason I’m able to take this stance and speak up is because I’ve been empowered by education, and that I was born to an educated mother.

I don’t need data to make the case that education is one of life’s greatest differentiators. I have to look no further than my own mother’s life to see how it alters life’s outcomes. One educated girl can change everything.

Like the other girls, Priscilla would have to wait until Sunday—two full days—before she could embrace her mother and father. When the moment finally came, it was at a specially arranged Thanksgiving service. At last, all the parents and daughters gazed on faces they’d long feared were lost to them forever. Under the cream-colored canopies erected to protect the families and specially invited VIPs from the unfriendly skies, mothers and fathers clung to their painfully thin daughters for the first time in years. They cradled their children like they were fragile newborns, as if the opening up of any space between them might allow something terrible to happen once more.

For Esther Yakubu, there has been no progress; she doesn’t have stories of her daughter’s healing to share. More than four years have passed since Dorcas disappeared, and Esther continues to count the days until her beloved returns. During these long years of separation, this mother of five has slowly morphed into a ghost of her former self. All joy has ebbed away, leaving her lifeless. She laments that God keeps her in a world without her firstborn by her side. She does her best to wade through the unending anguish, to be present for her remaining four children, all of whom miss their big sister terribly. They also mourn the mother they lost the day that Dorcas disappeared.

No comments:

Post a Comment