Too Short for a Blog Post, Too Long for a Tweet 304

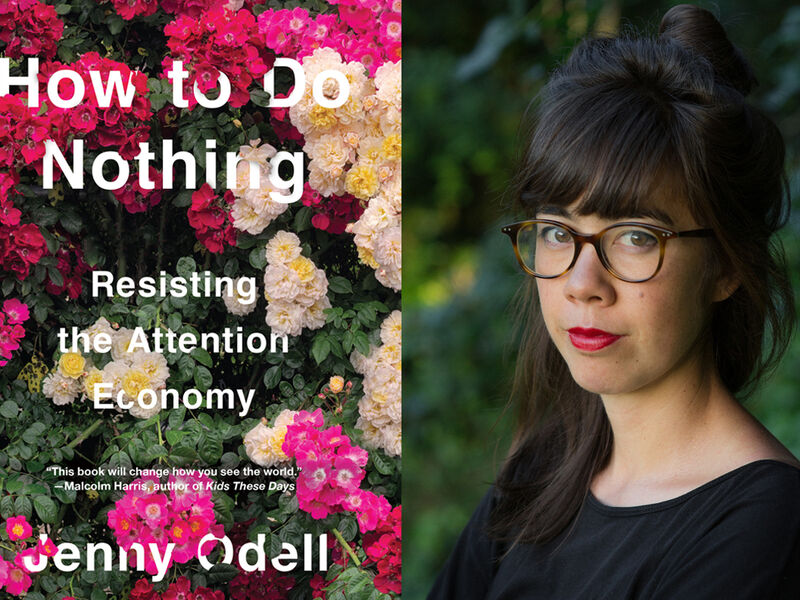

Here are a few excerpts from a book I recently read, "How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy," by Jenny Odell.

The first half of “doing nothing” is about disengaging

from the attention economy; the other half is about reengaging with

something else. That “something else” is nothing less than time and

space, a possibility only once we meet each other there on the level of

attention. Ultimately, against the placelessness of an optimized life

spent online, I want to argue for a new “placefulness” that yields

sensitivity and responsibility to the historical (what happened here)

and the ecological (who and what lives, or lived, here).

In

the process of writing this book, I realized that the experience of

research is exactly opposite to the way I usually often encounter

information online. When you research a subject, you make a series of

important decisions, not least what it is you want to research, and you

make a commitment to spend time finding information that doesn’t

immediately present itself. You seek out different sources that you

understand may be biased for various reasons. The very structure of the

library, which I used in Chapter 2 as an example of a noncommercial and

non-“productive” space so often under threat of closure, allows for

browsing and close attention. Nothing could be more different from the

news feed, where these aspects of information—provenance,

trustworthiness, or what the hell it’s even about—are neither internally

coherent nor subject to my judgment. Instead this information throws

itself at me in no particular order, auto-playing videos and grabbing me

with headlines. And behind the scenes, it’s me who’s being researched.

It’s

a bit like falling in love—that terrifying realization that your fate

is linked to someone else’s, that you are no longer your own. But isn’t

that closer to the truth anyway? Our fates are linked, to each other, to

the places where we are, and everyone and everything that lives in

them. How much more real my responsibility feels when I think about it

this way! This is more than just an abstract understanding that our

survival is threatened by global warming, or even a cerebral

appreciation for other living beings and systems. Instead this is an

urgent, personal recognition that my emotional and physical survival are

bound up with these “strangers,” not just now, but for life.

It’s

scary, but I wouldn’t have it any other way. That same relationship to

the richness of place lets me partake of it too, allowing me to

shape-shift like the flocks of birds, to flow inland and out to sea, to

rise and fall, to breathe. It’s a vital reminder that as a human, I am

heir to this complexity—that I was born, not engineered. That’s why,

when I worry about the estuary’s diversity, I am also worrying about my

own diversity—about having the best, most alive parts of myself paved

over by a ruthless logic of use. When I worry about the birds, I am also

worrying about watching all my possible selves go extinct. And when I

worry that no one will see the value of these murky waters, it is also a

worry that I will be stripped of my own unusable parts, my own

mysteries, and my own depths.

Comments