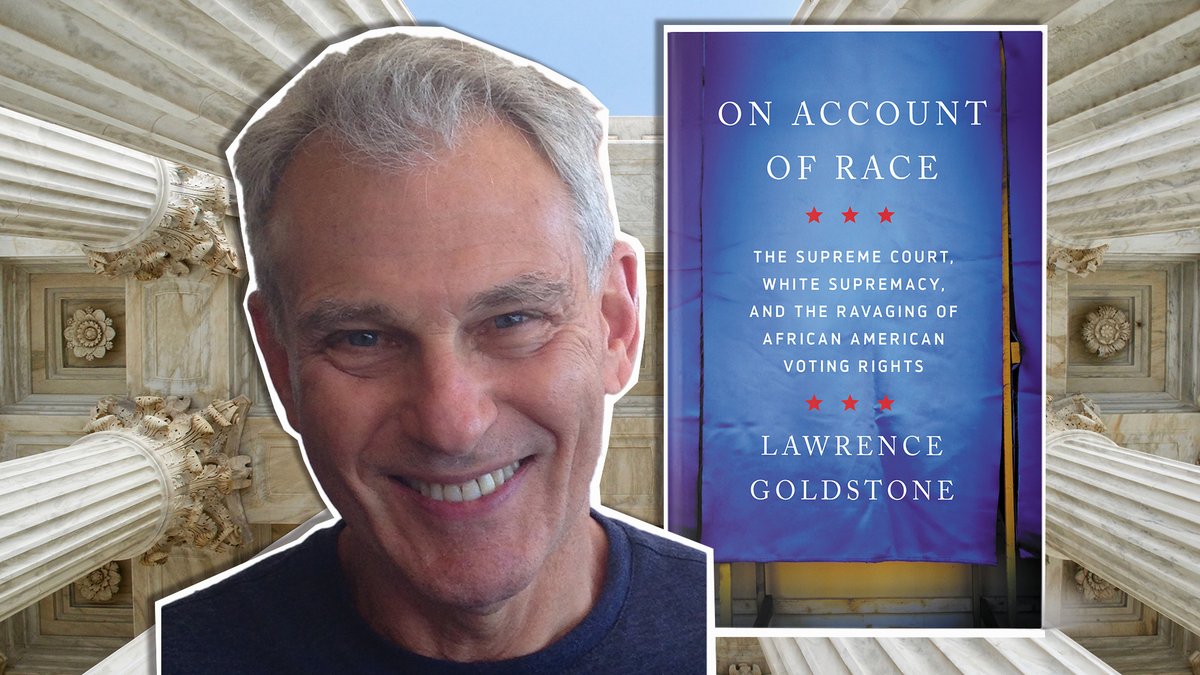

Here are a few excerpts from a book I recently read, "On Account of Race The Supreme Court, White Supremacy, and the Ravaging of African American Voting Rights," by Lawrence Goldstone.

When the soldiers marched out of the South, they took Reconstruction with them.

Louisianans, like their Redeemer brethren, thought of purging black Americans from the political process as a higher calling. When convention president Ernest B. Kruttschnitt addressed his fellow delegates during the convention’s opening session on February 8, 1898, in the Mechanics Institute in New Orleans, he intoned, “May this hall, where, thirty-two years ago the negro first entered upon the unequal contest for supremacy, and which had been reddened with his blood”—referring to an 1866 riot at which thirty-four freedmen had been murdered—“now witness the elevation of our organic law which will establish the relation between the races upon an everlasting foundation of right and justice.” In case his message had not been clear enough, he added, “We are all aware that this convention has been called by the people of the state of Louisiana principally to deal with one question . . . to eliminate from the electorate the mass of corrupt and illiterate voters who have during the last quarter of a century degraded our politics.”

Kruttschnitt was on record as declaring that Louisiana “could do better than the state of Mississippi,” and he felt similarly about South Carolina. The Mississippi and South Carolina Constitutions “lost their popularity when it became known that they would also disfranchise 20,000 white voters in the state. Louisiana was determined to go a step further and disfranchise the negro without sacrificing her white citizens who had the misfortune of being illiterate.”

After the convention concluded, The Times-Democrat editorialized the result. Without a hint of irony, the editor wrote,

The convention was called (1) to secure white supremacy for all time in Louisiana, and (2) to assure honest elections and put an end to the frauds which have so long debauched the public sense of the State. The frauds have been excused heretofore on the ground that they were necessary to white supremacy. With that supremacy secure by means of a new honest suffrage, all trickery becomes unnecessary, and we can have honest elections.

As in Mississippi and South Carolina, Louisiana African Americans did not sit by and passively accept what was happening. As they would in all the states that would alter their constitutions, blacks fought furiously to maintain their right to vote. The problem was not will; it was weaponry. They had no allies—not the president; not Congress; and certainly not the courts. They were fighting an enemy with vastly more resources, virtually all the power to employ them at will, an unbreakable belief in their own righteousness, and determination to succeed that would not be mitigated by morality, pity, or even religious dogma. So African Americans were reduced to futile attempts to influence the registration process and even more futile attempts to influence the white supremacists who controlled it. During the convention, Booker T. Washington, likely the most respected black man in the nation—at least among whites—wrote an open letter to the convention that was published in newspapers across Louisiana.

The Negro does not object to an educational or property test, but let the law be so clear that no one clothed with state authority will be tempted to perjure and degrade himself by putting one interpretation upon it for the white man and another for the black man . . . I beg of you, further, that in the degree that you close the ballot box against the ignorant that you open the school house. More than half of the population of your State are Negroes. No state can long prosper when a large part of its citizenship is in ignorance and poverty and has no interest in the government. I beg of you that you do not treat us as an alien people. We are not aliens.

But, as Washington seemed to realize, to the white supremacists who were meeting at the Mechanics Institute, black people were precisely that.

No comments:

Post a Comment