Too Short for a Blog Post, Too Long for a Tweet 222

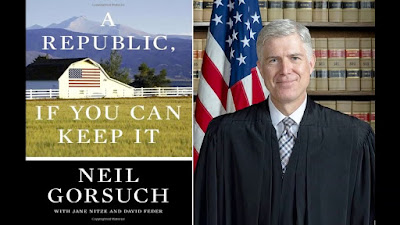

Here are a few excerpts from a book I recently read, "A Republic, If You Can Keep It," by Supreme Court Justice Neil Gorsuch.

Here are a few excerpts from a book I recently read, "A Republic, If You Can Keep It," by Supreme Court Justice Neil Gorsuch.By the end of it all, I came to realize that some today perceive a judge to be just like a politician who can and must promise (and then deliver) policy outcomes that favor certain groups. They see the job of a judge as less about following the law and facts wherever they lead and more about doing whatever it takes to “help” this group or “stop” that policy. And it struck me: It’s one thing to worry some judges might aggrandize their personal preferences over a faithful adherence to the law; but it’s another thing to think judges should behave like that.

The idea that judges do—and should—allow their policy preferences to determine their legal rulings was foreign to my experience in the law. The judges I admired as a lawyer and those I have come to cherish as colleagues know that Lady Justice is portrayed with a blindfold for a reason. These judges strive every day to ensure that their decisions aren’t based on which persons or groups they happen to like or what policies they happen to prefer. They don’t pretend to be philosopher-kings with the right or ability to pronounce judgment on all of society’s problems. They never boast that they can foresee all the (often unintended) consequences of their decisions, let alone accurately calculate the optimal social policy outcome. They don’t seek favor or fear condemnation but recognize instead that the judge’s job is only to apply the law’s terms as faithfully as possible.

To protect the rights of the people, the founders designed a Constitution that cedes to the central government only certain limited and enumerated powers that are, in turn, carefully separated and balanced. To the people’s representatives in Congress, the framers gave the power to make new laws restricting liberty—but at the same time they insisted that our representatives follow a deliberate and difficult process designed to achieve broad consensus before any new law might emerge. To ensure that the laws able to survive this careful process are vigorously enforced, the framers gave the power to execute the law to a single president rather than trust management-by-committee—but they also sought to ensure that the president could never arrogate the power to make laws or judge persons under them. Finally, to guarantee that all persons, regardless of their popularity or prestige, would enjoy the benefit of the laws when disputes arise, the framers created an independent judiciary—but they insisted, too, that judges insulated from democratic processes must have no role in lawmaking and should be counterbalanced with juries composed of the people. In all these ways, the framers recognized that each branch had not only a virtue to offer but also a vice to guard against.

Our founders never knew the Kim family of North Korea, but they had plenty of experience with a tyrannical ruler. More than a few in the founding generation suffered at the hands of a capricious king, thrown in jail (or worse) without a fair trial. From their own experience and understanding of history, the framers knew that to prevent the rule of law from becoming the rule of men more is required than a Constitution full of nice promises. What’s needed is a Constitution that counteracts the instinct to seek and misuse power, one that secures individual rights not so much by their enumeration as by real structural limits on the power of government and those who run it.

The Constitution is short—only about 7,500 words, including all its amendments. It doesn’t dictate much about the burning social and political questions they care about. Instead, it leaves the resolution of those matters to elections and votes and the amendment process. And it seems this is the real problem for the critics. For when it comes to the social and political questions of the day they care most about, many living constitutionalists would prefer to have philosopher-king judges swoop down from their marble palace to ordain answers rather than allow the people and their representatives to discuss, debate, and resolve them. You could even say the real complaint here is with our democracy.

A similar story unfolded in Wisconsin Central v. United States. There, we confronted the Railroad Retirement Tax Act of 1937. The statute allows the government to tax railroad employees’ “money” income. The government argued that this provision permitted it to tax the stock options an employee receives from his employer. As a matter of ordinary usage, of course, the term “money” meant then (as it does now) “a medium of exchange.” And pretty obviously, “stock” isn’t a medium of exchange; after all, no one buys groceries or pays rent in stock. Of course, stock can be converted into money. But then again, so can baseball cards. The truth is, most anything can be converted into money. Yet no one would seriously suggest that everything is money.

Maybe so, the government responded. But, it argued, there are strong purposivist and consequentialist reasons for eliding the difference between money and things convertible into money. If the statute’s purpose was to tax money income, it said, then we should follow that thought to its logical end and allow other things easily convertible into money to be taxable too. Distinguishing between monetary and nonmonetary income might, as well, yield a suboptimal tax policy by encouraging companies to award more remuneration in stock and less in money, leaving the federal fisc to suffer.

The Court rejected the government’s arguments. It explained that the judicial power doesn’t include a power to steer tax policy or pursue every good idea found in legislation to its logical conclusion or update statutes we think outdated. Nor is it a power to flatten out legislative compromises found in one area of the law but not another. That Congress chose to tax nonmonetary income elsewhere in the tax code showed that it knew very well how to do so if it wished. So we invoked the familiar textualist canon of interpretation that the expression of an idea in one place means its absence in another must be given effect. The fact that Congress made different choices in different statutes, we said, deserved respect, not a rewrite.

Notice the strong temptation judges face in both cases to revise the statute. To bend the statutory terms to reach a short-term policy victory for a popular whistleblower or against an unpopular tax-avoiding corporate shareholder. To feel like they’ve “made a difference.” Because textualism is value-neutral, it hands out victories based on the strength of consistency with a statutory text, not passing popularity. So, yes, one day textualism means the criminal defendant should win and the next day a corporate railroad shareholder must. Judges may not like every policy outcome they reach. But if they did, we should think less of them.

I respect, too, the fact that in our legal order, it is for Congress and not the courts to write new laws. It is the role of judges to apply, not alter, the work of the people’s representatives. A judge who likes every outcome he reaches is very likely a bad judge, stretching for results he prefers rather than those the law demands.

SENATOR SASSE: So, when you distinguish between the rearview mirror of a justice later or a judge later in life looking back, and the rearview mirror of a senator, we have different callings. Unpack that for the American people. Help them understand how the retrospective look of a senator and her or his career is different than a judge’s retrospective look.

JUDGE GORSUCH: I presume gingerly that you will look back on your career and say I accomplished this piece of legislation or that piece of legislation and changed the lives of the American people dramatically as a result. But as a judge looking back, the most you can hope for is you have done fairness to each person who has come before you, decided each case on the facts and the law, and that you have just carried on the tradition of a neutral, impartial judiciary. That is what we do. We just resolve cases and controversies. Lawyers are supposed to be fierce advocates, and I was once a fierce advocate for my clients. But a judge is supposed to listen courteously and rule impartially. So, frankly, my legacy should look and will look a lot smaller than yours, and that is the way it should be. That is the way the Constitution works.

Comments