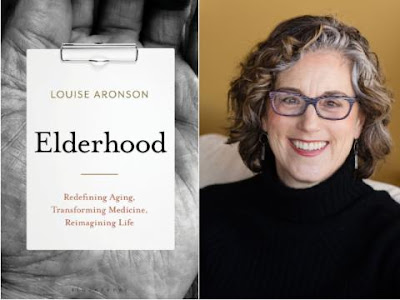

Here are a few excerpts from a book I recently read, "Elderhood: Redefining Aging, Transforming Medicine, Reimagining Life," by Louise Aronson.

Here are a few excerpts from a book I recently read, "Elderhood: Redefining Aging, Transforming Medicine, Reimagining Life," by Louise Aronson.

When I first walked into a pediatric ward as a medical student, a body blow of sensory memories time-traveled me from almost-doctor to small-sick-child and that world of cold walls, tall strangers, acrid odors of medications, antiseptics, and bodies, the endless refrains of beeps, moans, whispers, pain, and unknowing and wordless long, lonely nights. My summer of sickness taught me things a doctor needs to know about what care is and is not, and what it’s like to be sick and disabled in our ability-obsessed world, and how pain can be so bad that you would do anything to make it go away. It taught me what it’s like to be frail and small and vulnerable, and what kindness looks like, and cruelty, and how very much parents love their children, and what medicine can do when its tools fit a problem. And it taught me how wonderful it is to be alive and healthy, and that a great trauma can be transformative in ways both good and bad.

In a health care system where time is the scarcest resource and care is fragmented among doctors without a clear mechanism for designating a recognized team captain, new symptoms are too often attributed to age and disease rather than to the care or drugs that actually caused them.

Similar sentiments are common in patient care. Although older patients are by no means the only ones to elicit them, the very old do move slowly and often have more issues in need of attention. As a result, they require the one entity that constantly feels in short supply in modern life: time. The ticking clock creates tension, and the best way to relieve the tension is to get rid of whatever is slowing you down and move on, telling yourself the slowness isn’t your problem and is hampering your ability to meet your responsibilities. That’s the mind-set that leads doctors to cut patients of all ages off after just twelve to twenty-three seconds, cabbies to drive away from an old woman standing in the dark and cold, and people to roll their eyes as an older adult moves slowly down the street or unhurriedly produces their credit card at the grocery store. In all those situations, it’s easy to forget that efficiency is a concept best applied to organizations and systems, not people and human interactions.

It’s a rare family in which at least one person doesn’t know how to care for a child. Yet, though birth and death occur in human lives in a 1:1 ratio, and human mortality is holding steady at 100 percent, it’s common for no one in a family to know how to help someone die. This wasn’t always the case: for millennia people died at home.21 With the medicalization of aging and dying after World War II, that changed. By the 1980s, five out of six deaths took place in hospitals.22 Generations grew to and through adulthood without seeing or helping with a death. In the 1990s the trend began to reverse. In 1974 there was a single hospice agency in the United States; by 2013 there were 5,800. Now one in three deaths occur at home,23 and over 80 percent of hospice patients in the United States are over age sixty-five.

When it comes to death, patients and families often don’t know what to expect; not having been to medical or nursing school, they rely on their nurses and doctors for guidance. Ironically, despite the medicalization of dying, most doctors have little training in death.

Medicine still largely sees death as its adversary, instead of positioning itself as a tool to help ease that inevitable transition. Education about how to talk with patients and families about difficult decisions, bad news, and death only became standard in medical schools in the 2010s. It still isn’t a required part of residency training in most specialties or subspecialties.

No comments:

Post a Comment