Too Short for a Blog Post, Too Long for a Tweet 225

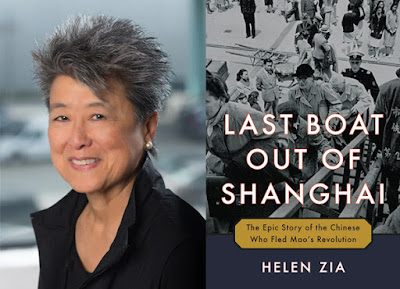

Here are a few excerpts from a book I recently read, "Last Boat Out of Shanghai: The Epic Story of the Chinese Who Fled Mao's Revolution," by Helen Zia.

Here are a few excerpts from a book I recently read, "Last Boat Out of Shanghai: The Epic Story of the Chinese Who Fled Mao's Revolution," by Helen Zia.

Unlike the stories of other such mass migrations from revolutions and human crises, the exodus of Chinese from Shanghai in this era has yet to be told. There are no books or dissertations in English that track their saga through the geopolitical tectonics of modern China. In the Chinese language, only a handful of accounts have been published—in Taiwan. Even today, the People’s Republic of China fails to acknowledge that any exodus took place.

The people of Shanghai in particular feared the Communists’ wrath. The very nature of their metropolis was forged from China’s century of humiliation imposed by the opium-peddling British, Americans, and other foreigners. Shanghai was a bastard city: too Western to be Chinese and too Chinese to be Western. The Bund, Shanghai’s fabled waterfront, looked more like a postcard from Europe than from China. Shanghai’s capitalist traditions and privileged urbanites encouraged a sensibility that welcomed modernity to this city “on the sea”—the literal meaning of the words shang hai.

To the Communists, modern was synonymous with Western, while Western was interchangeable with foreign. Westernized Shanghainese were nothing but yang nu and zou gou—foreign slaves and imperialist running dogs. Shanghai’s wealthy and middle classes, intellectuals and Nationalist partisans were certain to become targets in the coming Communist revolution.

By the time the Red Army surrounded Shanghai, waves of people had bolted: the city’s upper classes, the educated and resourceful, residents who had bet on the old guard—anyone who had anything to fear. Like the White Russians who had vanished from Bolshevik Moscow, the German Jews who had escaped Hitler’s Berlin, Vietnamese waiting for helicopters on the roof of the U.S. embassy in Saigon, or Syrians dodging bombs and bullets to brave the Mediterranean Sea, they fled: By boats so heavily laden they could not avoid collisions at sea; by planes so overweight they could not clear obstacles ahead; by trains with so many people clinging to every surface, the cars could only creep forward. Many had to flee in a frenzied rush, taking only what they could carry. Exile from their beloved city would be tolerable only because they expected to be gone no more than six months or a year at most. That was the longest they figured the Communist peasants would last, never imagining that more than thirty years would pass before they could return and reunite with loved ones.

Even without definitive records on the numbers of those who fled Shanghai, the magnitude of the exodus can be estimated from the counts of refugees that swelled in other regions. Hong Kong’s population doubled in 1949, increasing by more than a million refugees in that single year. In Taiwan, approximately 1.3 million to 2 million “mainlanders” descended on the small, largely rural island: Incoming Chinese Nationalist officials, retreating soldiers, loyalists, and their families thrust themselves onto the existing society of 9 million Taiwanese, taking total control of the island. Many thousands of other Chinese dispersed to Southeast Asia—Indonesia, the Philippines, Malaysia, Singapore, Burma, Vietnam—and as far as South America, Africa, and India. Only a trickle could enter the United States or Britain, with their long histories of restrictions against Asian immigrants, and even fewer went to Australia because of its virulent “whites only” policy.

The exodus out of Shanghai, like other human stampedes from danger, scattered its desperate migrants to any corner of the world where they might weather the storm. Seven decades later, stories of courage, strength, and resilience have emerged from the Shanghai exodus, offering a glimmer of insight, even hope, to newer waves of refugees who are struggling to stay afloat in the riptides of history.

The unkindest cuts came from the children of the servants, who, taking their cues from their parents, were relentless in their torment. “Nobody wants you! Your family gave you away!” they taunted. They ridiculed her new name, a homonym of the Chinese word for bottle.“You’re a bing, an empty bottle. A nothing, a nobody.” They took every opportunity to pick at her. Bing wanted to run and hide whenever she saw them, but there was no escape. She grew to hate her name and its constant reminder of her shame.

The nine-year-old had assumed that she would be going to Chongqing. But Mama presented her with a terrible choice: Bing could come along with Mama Hsu on the dangerous journey, which would be many times more arduous for a child, Mama told her. Or Bing could stay in Shanghai, and Mama Hsu would find her a new family to live with. “It’s your choice. Which do you prefer?” she asked.

The old hole in Bing’s heart ripped open again. Her sadness and shame at being an unwanted girl had never truly left her, and now it came flooding back. She could no longer remember where she had lived in Changzhou. She didn’t know her own birth date. The names and faces of her first family—even her baba’s—had gradually sifted from her memory. But she was certain of one thing: If Mama really wanted her, she would never have posed such a question. A real mother would take her real daughter with her—that much Bing knew.

It took only a few seconds for Bing to answer. She shrugged her small shoulders and stiffened the shell around her heart. Then she gave the answer she thought Mama wanted to hear: “I guess I’ll stay in Shanghai.”

When Mama didn’t try to dissuade her, the heartbroken girl knew she had been right.

To bypass the censors, some correspondents resorted to code. One educated member of Shanghai’s social set, having decided not to leave his home, arranged to send a message in a photo to his family, who had fled overseas: If he was standing, all was well. If he was sitting, things were bad. When he finally sent them a picture, he was lying down.

Comments