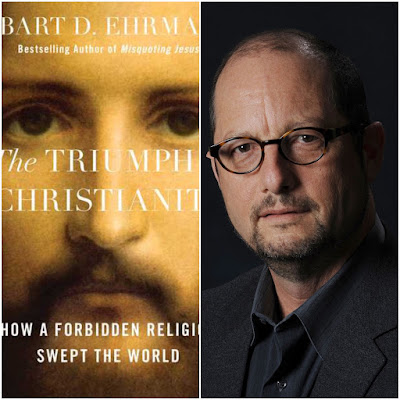

Here are a few excerpts from a book I recently read, "The Triumph of Christianity: How a Forbidden Religion Swept the World," by Bart Ehrman.

Here are a few excerpts from a book I recently read, "The Triumph of Christianity: How a Forbidden Religion Swept the World," by Bart Ehrman.

Before

the triumph of Christianity, the Roman Empire was phenomenally diverse,

but its inhabitants shared a number of cultural and ethical

assumptions. If one word could encapsulate the common social, political,

and personal ethic of the time, it would be “dominance.”

In

a culture of dominance, those with power are expected to assert their

will over those who are weaker. Rulers are to dominate their subjects,

patrons their clients, masters their slaves, men their women.

This

ideology was not merely a cynical grab for power or a conscious mode of

oppression. It was the commonsense, millennia-old view that virtually

everyone accepted and shared, including the weak and marginalized. This

ideology affected both social relations and governmental policy. It made

slavery a virtually unquestioned institution promoting the good of

society; it made the male head of the household a sovereign despot over

all those under him; it made wars of conquest, and the slaughter they

entailed, natural and sensible for the well-being of the valued part of

the human race (that is, those invested with power).

With

such an ideology one would not expect to find governmental welfare

programs to assist weaker members of society: the poor, homeless,

hungry, or oppressed. One would not expect to find hospitals to assist

the sick, injured, or dying. One would not expect to find private

institutions of charity designed to help those in need.

The

Roman world did not have such things. Christians, however, advocated a

different ideology. Leaders of the Christian church preached and urged

an ethic of love and service. One person was not more important than

another. All were on the same footing before God: the master was no more

significant than the slave, the patron than the client, the husband

than the wife, the powerful than the weak, or the robust than the

diseased. Whether those Christian ideals worked themselves out in

practice is another question. Christians sometimes—indeed, many

times—spectacularly failed to match their pious sentiments with concrete

actions, or, even more, acted in ways contrary to their stated ideals.

But the ideals were nonetheless ensconced in their tradition—widely and

publicly proclaimed by the leaders of the movement—in ways not

extensively found elsewhere in Roman society.

As

Christians came to occupy positions of power, these ideals made their

way into people’s social lives, into private institutions meant to

encapsulate them, and into governmental policy. The very idea that

society should serve the poor, the sick, and the marginalized became a

distinctively Christian concern. Without the conquest of Christianity,

we may well never have had institutionalized welfare for the poor or

organized health care for the sick. Billions of people may never have

embraced the idea that society should serve the marginalized or be

concerned with the well-being of the needy, values that most of us in

the West have simply assumed are “human” values.

This

is not to say that Judaism, the religion from which Christianity

emerged, was any less concerned with the obligations to “love your

neighbor as yourself” and “do unto others as you would have them do unto

you.” But neither Judaism nor, needless to say, any of the other great

religions of the world took over the empire and became the dominant

religion of the West. It was Christianity that became dominant and, once

dominant, advocated an ideology not of dominance but of love and

service. This affected the history of the West in ways that simply

cannot be calculated.

Despite their differences, all these expectations of the coming messiah had one thing in common: he was to be a figure of grandeur and power who would overthrow the enemies of Israel with a show of force and rule the people of God with a powerful presence as a sovereign state in the Promised Land.

And who was Jesus? He was a crucified criminal. He appeared in public as an insignificant and relatively unknown apocalyptic preacher from a rural part of the northern hinterlands. At the end of his life he made a pilgrimage to Jerusalem with a handful of followers. While there, he ended up on the wrong side of the law and was unceremoniously tried, convicted, and tortured to death on criminal charges. That was the messiah? That was just the opposite of the messiah.

There are good reasons for thinking that during his lifetime, some of Jesus’s followers thought maybe he would be the messiah. Those hopes were forcefully and convincingly dashed by his execution, since the messiah was not to be executed. But some of these followers came to think that after his death a great miracle had occurred and God had brought Jesus back to life and exalted him up to heaven. This belief reconfirmed the earlier expectation: Jesus was the one favored of God. He was the anointed one. He was the messiah.

This reconfirmation of a hope that had been previously dashed compelled these early followers of Jesus to make sense of it all through the ultimate source of religious truth, their sacred scriptural traditions. They found passages that spoke of someone—a righteous person or the nation of Israel as a whole—suffering who was then vindicated by God. These included passages such as Isaiah 53, quoted earlier. The followers of Jesus claimed such passages actually referred to the future messiah. They were predictions of Jesus.

This was for them “good news.” Jesus was the messiah, but not one anybody had expected. By raising Jesus from the dead, God showed that his death had brought about a much greater salvation than anyone had anticipated. Jesus did not come to save God’s people from their oppression by a foreign power; he came to save them for eternal life. This is what the earliest Christians proclaimed.

For the zealous Pharisee Paul, it was utter nonsense—even worse: it was a horrific and dangerous blasphemy against the Scriptures and God himself. This scandalous preaching had to be stopped.

The entire letter to the Galatians is predicated on the fact that the readers are gentile Christians being told by false teachers to begin practicing the ways of Judaism. These are all churches filled with pagan converts. So where did Paul meet them?

Modern scholarship has landed on a solution that is both sensible and supported by Paul’s own words. In his letter to the Thessalonians, Paul recalls preaching while engaged in manual labor: “For you remember, brothers and sisters our labor and toil; during night and day we labored so as not to burden you, preaching to you the gospel of God” (1 Thessalonians 2:9). When he refers to his toil here, it is not to his toil of preaching: it was toil that kept him from having to be supported financially by others. He was working both a day and a night job. So too in his letter to the Corinthians, Paul stresses that he and his missionary companions engaged in a life of “labor, working with our own hands” (1 Corinthians 4:12). Later he reminds them how he and his companion Barnabas had “to work for a living” (9:6).

And so the question is, how are we to imagine the relationship between Paul’s daily work and his missionary activity? New Testament scholar Ronald Hock has argued the most persuasive case: Paul was preaching on the job.

Support for this view comes from the book of Acts, which indicates that Paul was a professional “tentmaker” (Acts 18:3). Some scholars have thought this word can have broader applicability, referring to some kind of leather-goods work. (Tents were made from animal skins, but so obviously were lots of other things.) There is no certainty on the matter. But it does appear that Paul was a craftsman of some kind. If so, we can have a good idea of how he proceeded from one town to the next establishing churches. If he was a leather- worker Paul would have had a mobile profession. He would have taken his knives, awls, and other tools of the trade with him from one place to the next. When coming to a new town, he would meet up with others in his line of work. Commonly the professions were centered in one part of the city or another. He would choose an apt spot, rent out a space for his workshop, probably secure an apartment in a floor above for living quarters (this was common in city dwellings: a multilevel building of this sort was called an insula), and open up for business.

It is in some such context that he would have “preached night and day” to the Thessalonians. People would come into his shop for business and he would talk to them about religion. Businesses as a rule were far more casual in that way than today. People could spend a long time in conversation. Paul, by his own account, was at it at all hours. Obviously he would not be able to convert someone the first time they met, on the spot. He was urging pagan people to give up every religious tradition and cultic practice they had ever known. That took time. But he had time. He had to work—he was at it before dawn to after dusk—and while working with his hands he was preaching the gospel.

There should be some term that would differentiate between the belief in only one true god—the strict definition of monotheism—and the worship of one god to the exclusion of all others, who are seen, nonetheless, to be gods. That is the term I have already used and will continue to use, “henotheism.” I will contend that the growing popularity of henotheism in the empire paved the way for the Christian declaration that there is in fact only one god and he alone should be worshiped.

Nonetheless, there is very little evidence to suggest that Jews actively sought converts or partial converts. Outsiders may have been attracted to aspects of Jewish worship and life, but most Jews were content to observe their traditional customs and forms of worship themselves and to let pagans do whatever pagans chose to do. This view has been argued convincingly by a number of recent scholars, including ancient historian Martin Goodman, who on the basis of a thorough examination of every significant piece of ancient pagan and Jewish evidence has concluded that the evangelizing mission of the Christian church was unparalleled and unprecedented: “Such a proselytizing mission was a shocking novelty in the ancient world.”

This mission of evangelism, as we will see, became a standard feature of the Christian movement and eventually, for many Christians, a contest for converts. But significantly, as Goodman explains, “For most of the period before Constantine’s conversion, such Christians will have been running in a race of whose existence most of the other competitors were unaware.”

If the concerted attempt to win converts was not a standard feature of ancient religion, even Judaism, why did Christianity become missionary? Even though our ancient sources provide us with no firm answer, some informed intuition would suggest that surely it had to do with the nature of the Christian message. Christians as early as Paul—the first to undertake a worldwide mission—maintained that Christ died because it was God’s plan to bring salvation to the world. Those who did not experience this salvation were lost, doomed to punishment. As an apocalyptic Jew, Paul, and then his converts, insisted God was soon to enter into judgment with this world. A cataclysmic act of destruction was to occur. Those who were in Christ would be spared the onslaught and be brought into God’s eternal kingdom. Those who were not would be destroyed. Some Christians insisted the coming cataclysm was not simply an annihilation in which a person would cease to exist. It was to entail ongoing punishment, eternal torment.

At the same time, Christianity prided itself as a religion of love. Jesus was remembered as one who taught his followers to love God above all things, but also, next, to love their neighbors as themselves. By “neighbor” he did not simply mean the person next door. Everyone is a neighbor. Even an enemy is a neighbor. Christians were to love everyone in the world, even those who detested, opposed, and persecuted them.

If God commands his people to love others and, consequently, to act in ways that will benefit them, and if others are destined to the coming divine judgment unless they turn to God in repentance and begin to worship him alone, there is only one clear conclusion: Christians need to urge others to adopt their religion. It is the only way these others will be saved, the only way they can escape eternal punishment. It is therefore the only way a Christian can really show love for the other.

Christians then, starting at least with Paul, came to be missionary, convinced they had to convert the world. Goodman maintains it was Paul himself who came up with the idea. He was the innovator, “the single apostle who invented the whole idea of a systematic conversion of the world, area by geographical area.” At the same time, this is what makes it so striking and unexpected that, outside of Paul’s work itself, we do not know of any organized Christian missionary work—not just for the first century, but for any century prior to the conversion of most of the empire. As MacMullen has succinctly put it: “After Saint Paul, the Church had no mission.”

That may be hard to believe, but in fact, if you were to count every Christian missionary about whom even a single story is told, from the period after the New Testament up through the first four centuries, you would not need all the digits on one hand: there is Gregory the “Wonderworker,” who worked not worldwide but in a small area of third-century Pontus, a province in what is now northern Turkey; Martin of Tours, a fourth-century bishop who converted pagans in his own city of Tours in France; and Porphyry, a late-fourth-century bishop who closed pagan temples in Gaza and converted their devotees. We are not talking about armies of volunteers knocking on doors. We know of three, all in a different isolated region. And, as we will see, even the stories told of them are highly legendary.

If Christians did not convert others through organized missionary efforts, how did they do it? The answer is simple: it was not by public preaching or door-to-door canvassing of strangers. They used their everyday social networks and converted people simply by word of mouth.

Social networks are all the human connections we have by virtue of the fact that each of us is a living, breathing human being who has a life. We have family. We have friends. We have neighbors. We know people at work. We see acquaintances on the street, at the store, and at sporting events. We belong to clubs and organizations. We participate in the life of our communities. In short, we have numerous connections in numerous ways with numerous people.

The people you know from different points of contact often know many other people you also know. And they know people you do not know. Those people you do not know may know some people you know and certainly others you do not. Social networks all overlap but they are never the same from one person to the next. The community comprises everyone networked into it in a wide range of ways.

That was true in the ancient world as well. Christians did not associate only with Christians. In the early centuries, most of the people Christians would have known would have been non-Christians. The way Christianity spread was principally through these networks.

A Christian woman talks about her newfound faith to a close friend. She tells the stories she has heard, stories about Jesus and about his followers. She also tells stories about her own life, how she has been helped after prayer to the Christian god. After a while, this other person expresses genuine interest. Over time she considers joining the church herself. When she does so, that opens up more possibilities of sharing the “good news,” because she too has friends. And family, neighbors, and people she sees in all sorts of contexts.

The woman converts. Over time she converts her husband. He insists the entire family—children, servants, slaves—follow the Christian religion. Three years later he ends up converting a business associate. That one requires his family as well to adopt the Christian faith. One of his teenage daughters eventually not only goes through the religious motions that her father requires (for example, saying prayers and going to the weekly church meeting) but becomes deeply committed. She converts her best friend. Who converts her mother. Who converts her husband. And then the next-door neighbor.

And so it goes. Year after year after year. One reason Christianity grows is that it is the only religion like this: the others are not missionary and they are not exclusive. These two features make Christianity unlike anything else on offer. The people who become Christian are turning their backs on their pagan pasts, their pagan customs, and their pagan gods. That means that virtually every new Christian is also an ex-pagan. Every new addition to the church means one less adherent to the old, traditional religions. As Christianity grows, it is destroying paganism in its wake.

And so Christianity was the only evangelistic religion that we know of in antiquity, and, along with Judaism, it was also the only one that was exclusive. That combination of evangelism and exclusion proved to be decisive for the triumph of Christianity. If it had been evangelistic but not exclusive, it may well have gained adherents, but paganism would have remained unaffected. Pagans would simply have begun to worship Christ along with whatever other gods they chose: Jupiter, Apollo, Diana, Mithras, Isis . . . take your pick. If, on the other hand, it had been exclusive but not evangelistic, Christianity, like Judaism, would have simply been an isolated and marginal religion without masses of adherents.

But it gained a massive following. Not at first, but over time, progressively adding to its ranks year after year, decade after decade. As it grew, paganism necessarily shrank. Unlike any religion known to the human race at the time, Christianity thrived by killing off its opposition.

Heedless of the danger, they took charge of the sick, attending to their every need and ministering to them in Christ, and with them departed this life serenely happy; for they were infected by others with the disease, drawing in themselves the sickness of their neighbors and cheerfully accepting their pains. Many, in nursing and curing others, transferred their death to themselves and died in their stead . . . . The best of our brothers lost their lives in this manner, a number of presbyters, deacons, and laymen.

He built his capital as an explicitly Christian city. There were to be no temples to pagan divinities and no sacred idols, with one exception: in order to adorn his city with statuary, a typical feature of the ancient urban environment, Constantine had sacred sites from around his empire pillaged, with bronze statues brought back and installed in public spaces throughout the city. This decision had a triple function: it deprived pagan religions of their revered cult images, it desacralized the statues and made them “secular” objects of art, and it raised the aesthetic appeal of his new capital. In the process, it gave the opportunity for Christians, whether resident or visiting, to mock the religious views of pagans.

No comments:

Post a Comment