Too Short for a Blog Post, Too Long for a Tweet 466

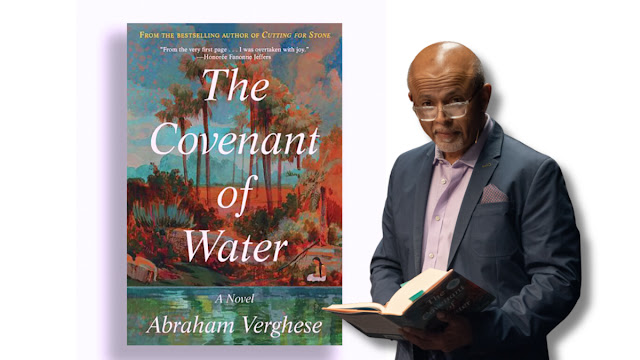

Here are a few excerpts from a book I recently read, "Covenant of Water," by Abraham Verghese.

The chaos and hurt in God’s world are unfathomable mysteries, yet the Bible shows her that there is order beneath. As her father would say, “Faith is to know the pattern is there, even though none is visible.”

The Zamorin of Calicut was quite unimpressed by da Gama, and by his monarch who sent sea corals and brass as tributes, when the zamorin’s presents were rubies, emeralds, and silk. He found it laughable that da Gama’s stated ambition was to bring Christ’s love to the heathens. Did the idiot not know that fourteen hundred years before his arrival in India, even before Saint Peter got to Rome, another of the twelve disciples—Saint Thomas—had landed just down the coast on an Arab trading dhow?

“You did famously. It’s the same operation as you did in Scotland, just that the pathology is magnified.”

That word captures Digby’s first impression of India. It’s a term he’ll use often when a familiar disease takes on grotesque proportions in the tropics: “magnified.”

A few weeks after they bury him, as life at Parambil struggles to find its new normal, she hears the sounds of digging and scratching in the courtyard just as she’s about to fall asleep. It stops. The next night, she hears it once more. She goes out to sit on the verandah, facing the sound. “Listen,” she says, “you must forgive me. I chastise myself for not coming to you after putting the children to bed. I fell asleep. I’m sorry we argued at dinner. I overreacted. Yes, I too wish it had been different. But it was just one night out of so many that were perfect, was it not? I hoped for many more perfect nights but each was a blessing. And listen: I forgive you. After a lifetime of goodness together, you were more than entitled to a tantrum. So be at peace!”

She listens. She knows he has heard her. Because, as was always his way, he expresses his love for her the only way he knows how: through his silence.

Even before his brain digests these sights, his body—skin, nerve endings, lungs, heart—recognizes the geography of his birth. He never understood how much it mattered. Every bit of this lush landscape is his; its every atom contains him. On this blessed strip of coast where Malayalam is spoken, the flesh and bones of his ancestors have leached into the soil, made their way into the trees, into the iridescent plumage of the parrots on swaying branches, and dispersed themselves into the breeze. He knows the names of the forty-two rivers running down from the mountains, one thousand two hundred miles of waterways, feeding the rich soil in between, and he is one with every atom of it.

They are perfectly matched, he thinks, both of them weathered by grief and time. And what is time but cumulative loss?

The next morning, before he opens his eyes, he thinks, Let this be a bad dream. Let me see my mother moving about, and my father holding the baby. But his father’s skin is as cold as stone. He has forgotten to breathe. His features are distorted from the blisters, and a puzzled expression is frozen on his face. His sister’s mouth moves like a fish out of water, her chest heaving sporadically, and as he watches, it comes to a stop. Lenin has never seen a dead body, but he knows he’s looking at two. His mother still breathes. Something breaks inside him. He flings the empty water vessel against the wall. He shakes his mother violently. “How can I manage if there’s no one to care for me?” He falls on her, weeping. “I’m your baby. Please, Amma, don’t leave me.” Her eyes are rolled back, unseeing. She’s beyond hearing.

It is hot outside, but he shivers with hunger and fear. Follow the straight path—that was the last thing his father said. He will do that. He will walk in a straight line till he gets food or drops dead. Nothing will stop him. If he comes to water . . . well then, he’ll drown.

The Condition now has a medical name and an anatomic location, which explain its strange symptoms: deafness, an aversion to water, and drowning. They’ve found the enemy, but the victory feels hollow. So what if they have a name for it? What use is that unless science and surgery can advance to where a child with this disorder can live a normal life without the risk of drowning, or hearing loss, or worse symptoms as they get older?

“Do you know, I only coined the name ‘Mar Thoma Medical Mission Hospital’? It flows like honey off the tongue, does it not? But before the foundation was poured, people shortened it to ‘Yem-Yem-Yem Hospital.’” Mariamma thinks it understandable: “M” on the Malayali tongue can come out as “Yem.” And Malayalis love acronyms. “Then they began calling it ‘Triple Yem Hospital’! Can you imagine? So vulgar, Triple Yem! Like some ointment for piles!” She doesn’t admit to him that Triple Yem has caught on—she’s as guilty as all the others.

Comments