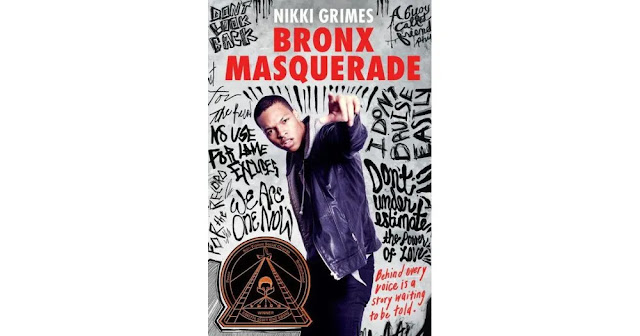

Here are a few excerpts from a book I recently read, "Bronx Masquerade," by Nikki Grimes.

That girl in the mirror, daughter of San Juan made of sunshine and sugarcane, looks like me.

She used to run, weightless,

Time a perfumed bottle hanging from her neck, mañana a song she made up the words to while she skipped— until the day she stopped, caught the toothless, squirming bundle heaven dropped into her arms and gravity kicked in.

Her life took a new spin.

This screaming gift did not lead her to dream places or fill all her empty spaces like she thought. Silly chica.

She bought into Hollywood’s lie, that love is mostly what you get instead of what you give, and what it costs, like the perfumed bottle ripped from her neck and sent flying to the ground.

The crashing sound of years lost shattered in her ears, and new fears emerged from the looking glass.

Sometimes I wonder if she’ll ever sing again.

“I’ve been meaning to tell you, I really liked the poem you read for Open Mike Friday.”

“Yeah? Well, thanks. I’m not used to writing poetry.”

“Well, nobody could tell it. You know, I could really get into what you were saying about trying to make yourself over, wishing you could be perfect and all. I mean, I feel like that every time I look in the mirror.”

Judianne nodded, and her tight mouth softened a little. She was about to say something, but then a toilet flushed and she realized we were not alone. Sheila Gamberoni came out of the stall, and the minute she did, Judianne slipped back behind her usual scowl and turned mean.

“Look, I am nothing like you, okay?” she spit out. “In case you haven’t noticed, you’re fat and I’m not. And you’re wrong about my poem. It was just words. It didn’t mean anything. You got that?” And she slammed out of the bathroom and left me there, stinging from the inside out.

I bit my lip to keep the tears back. I turned the faucet on and washed my hands a few times, staring at the sink until I heard Sheila step out into the hall. I glanced up at the mirror before I left. “You’re wrong, Judianne,” I said to the mirror. “They weren’t just words, and you know it.”

I haven’t tried talking with her since. I don’t want to give her an excuse to be mean to me again. I’m not mad at her, though. I know there’s a part of her that’s as scared to look in the mirror as I am. I saw that person for a few seconds, even if she wants to deny it. Calling me names won’t change the way she feels inside. One of these days, she’s going to find that out.

In case I forgot to tell you,

I’m allergic to boxes:

Black boxes, shoe boxes

New boxes, You boxes— Even cereal boxes

Boasting champions.

(It’s all a lie.

I’ve peeked inside

And what I found

Were flakes.)

Make no mistake,

I make no exceptions

For Cracker Jack

Or Christmas glitter.

Haven’t you noticed?

I’m made of skeleton,

Muscle and skin.

My body is the only box I belong in.

But you like your boxes

So keep them.

Mark them geek, wimp, bully.

Mark them china doll, brainiac,

Or plain dumb jock.

Choose whatever

Box you like, Mike.

Just don’t put me

In one, son.

Believe me, I won’t fit.

Everybody around me is dark and ethnic. Which is in, by the way. Look at all the supermodels. They’re from places like Venezuela and Africa and Puerto Rico. Then there’s me, white bread and pale as the moon. I can’t even tan without burning myself. I look around my neighborhood and this school, and nobody looks like me. I keep thinking if I could just stick out less, if I could learn to walk and talk like the kids around me, maybe I would fit in more. I don’t know. Maybe it’s a dumb idea. Wesley sure thinks so. When he pulled me aside in the school hall and I tried to explain why I was copying Porscha’s walk, stupid was the word he used. The minute he said it, I felt my cheeks go red. That’s not the color I was after. I jerked away from Wesley and avoided his eyes.

“Okay, maybe it was stupid. But I just want to fit in. I’m tired of being different, all right?” Suddenly I thought, Why am I trying to explain this to Wesley? He’s Black. He already fits in. “Forget it,” I said, beginning to walk away. “You don’t understand.”

“Oh, get a clue, girl! Everybody’s different. It don’t matter what your skin color is, or what name you call yourself. Everybody is different inside, anyway. We’re all trying to fit in. Ain’t nothing new about that.”

“Great!” I said. “Since you’re so smart, tell me what I’m supposed to do!”

Wesley shrugged. “Hey, I don’t know what to tell you, except be yourself.”

“Wonderful! Pearls of wisdom. Thanks a lot.”

Wesley put his hand on my shoulder. “Sheila,” he said, “you want to hang with brothas and sistas, it ain’t no big thing. Just don’t try to be them. Keep your name, change it—whatever. A name is a personal thing and I’m not going to get into that. But why you want to change who you are? Soon as you get out of here, you’re going to go to a college or get a job where everybody else is as blond and blue-eyed as you. They walk like you and talk like you. What’re you going to do, then? Change yourself back?”

The truth of his words pinned me to the wall. I never even stopped to think about the future, about leaving this school, this neighborhood, maybe even this city. All I ever think about is now, because now hurts so bad.

When I first got up to read, I was my usual self. I sucked in my stomach, walked slow to make sure nothing jiggled, and tugged down on my shirt, like I could really hide my extra pounds under there. I waited for Mr. Ward to switch on the video and then started to read.

I looked up from the page a few times and noticed kids in the front row with their eyes closed, smiling. Amy and Tanisha nodded every now and then, like I’d said something familiar, something they understood. Judianne, Leslie, and Porscha leaned forward so they could hear every word. Everybody really listened to what I had to say, even the guys. Tyrone, Wesley, Steve, Raul, Devon—they all stared at me like I was someone special. And nobody cared about the size of my body. Not even me.

No comments:

Post a Comment