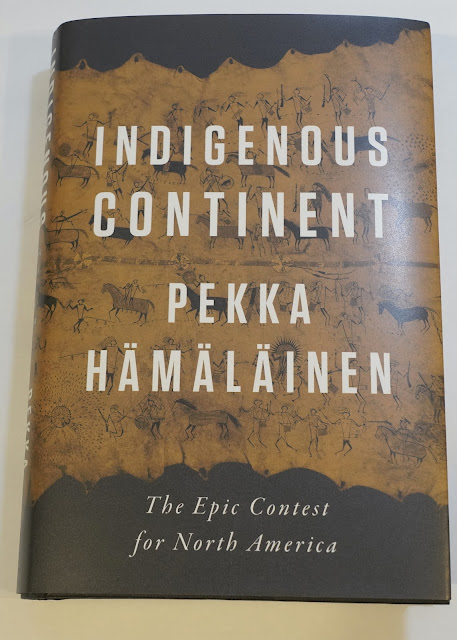

Here are a few excerpts from a book I recently read, "Indigenous Continent: The Epic Contest for North America," by Pekka Hämäläinen.

By 1776, various European colonial powers together claimed nearly all of the continent for themselves, but Indigenous peoples and powers controlled it. The maps in modern textbooks that paint much of early North America with neat, color-coded blocks confuse outlandish imperial claims for actual holdings. The history of the overwhelming and persisting Indigenous power recounted here remains largely unknown, and it is the biggest blind spot in common understandings of the American past.

This book is first and foremost a history of Indigenous peoples, but it is also a history of colonialism. The history of North America that emerges is of a place and an era shaped by warfare above all. The contest for the continent was, in essence, a four-centuries-long war that saw almost every Native nation fight encroaching colonial powers—sometimes in alliances, sometimes alone. Although the Indian wars in North America have been written about many times before, this book offers a broad Indigenous view of the conflict. For Native nations, war was often a last resort. In many cases, if not most, they attempted to bring Europeans into their fold, making them useful. These were not the actions of supplicants; the Europeans were the supplicants—their lives, movements, and ambitions determined by Native nations that drew the newcomers into their settlements and kinship networks, seeking trade and allies. Indian men and women alike were sophisticated diplomats, shrewd traders, and forceful leaders. The haughty Europeans assumed that the Indians were weak and uncivilized, only to find themselves forced to agree to humiliating terms—an inversion of common assumptions about White dominance and Indian dispossession that have survived to the present.

Kinship—an all-pervasive sense of relatedness and mutual obligations—became the central organizing principle for human life. Kinship was the crucial adhesive that kept people and nations linked together. It would be a mistake to see this adaptation as some kind of a failure or aberration of civilization, as European newcomers almost invariably did. North American Indians had experimented with ranked societies and all-powerful spiritual leaders and had found them deficient and dangerous. They had opted for more horizontal, participatory, and egalitarian ways of being in the world—a communal ethos available to everyone who was capable of proper thoughts and deeds and willing to share their possessions. Their ideal society was a boundless commonwealth that could be—at least in theory—extended to outsiders, infinitely.

Unknowingly, Columbus had brought together two parts of humankind that had been separated by oceans for several millennia. The Indigenous inhabitants may have appeared utterly alien and inferior to the Spanish, but the two sapiens contingents were genetically identical. All of their meaningful differences were cultural. Columbus may have been disillusioned, but he knew what he, a good European, should do. He came from a society where one’s position was determined largely by birth. One found purpose in preaching, fighting, or serving others. For Columbus and his contemporaries, there was little doubt where the Taínos belonged in that order. To Spanish eyes, they were primitive heathens living on an isolated island, and thus familiar: Spanish soldier-mariners had subdued similar people in the Canary Islands only a few decades earlier. The conquest of the Canaries had served as a laboratory of overseas imperialism, educating the Spanish in how to make strangers subjects, even slaves. Obsessed with gold, Columbus spent weeks in the West Indies hunting for it, and along the way he began to distinguish between good Indians and bad Indians. Good Indians were meek and made docile servants; bad Indians resisted Spanish demands and fought back. Good Indians could be converted; bad Indians should be enslaved. Columbus had given Spain a blueprint for a New World empire. After sailing back to Spain to secure royal support, he returned to America a year later with fifteen caravels, two smaller vessels, and fifteen hundred men. He had identified a new resource, and the Spanish promptly enslaved sixteen hundred Indians.

Perhaps the most difficult challenge facing the Indians was gauging how much success they could safely enjoy. The colonists wanted the Indians to accept their god, customs, and values, but too much adaptive acuity could be dangerous, provoking the English to see the Indians as competitors. If Indians managed to register their landholdings, they faced the threat of being labeled “Blacks” and having their claims abolished; if they thrived as farmers or livestock breeders, they risked incurring the wrath of their less capable English neighbors. For each Indian who managed to carve out a niche among the English, there were many more who were reduced to bound servitude or outright slavery.

Horses also overturned the power dynamics between the nomadic Indigenous nations and European colonists in the West. At its most basic level, this shift was a matter of harnessing energy. Dogs, Native Americans’ only domesticates before horses, were omnivorous and could use the West’s greatest resource—grass—only indirectly. They relied on their masters to provide them with the flesh of herbivorous animals, whereas horses, with their large and finely tuned intestines, could process vast quantities of cellulose-rich grass. The horse was a bigger and stronger dog, but, more profoundly, it was an energy converter. By transforming inaccessible plant energy into tangible and immediately available muscle power, horses opened up an astonishing shortcut to the sun, the source of all energy on Earth. For the Comanches the sun was “the primary cause of all living things,” and horses brought them closer to it, redefining what was possible: the biomass of the continental grasslands may have been a thousand times greater than that of the region’s animals. The Comanches plugged themselves into a seemingly inexhaustible energy stream of grass, flesh, and sunlight.5

The Lakotas had exposed the fiction at the center of the Corps of Discovery. Lewis and Clark tried to hold on to their conqueror narrative, in which they were asserting U.S. authority over the Missouri Valley, but in reality, the Lakotas were consolidating their supremacy over the valley in the expedition’s wake. Instead of extending the American empire into the deep interior of the continent, Lewis and Clark had provoked an awe-inspiring imperial Indigenous response that foiled the Jeffersonian vision for the continent.

.jfif)

No comments:

Post a Comment