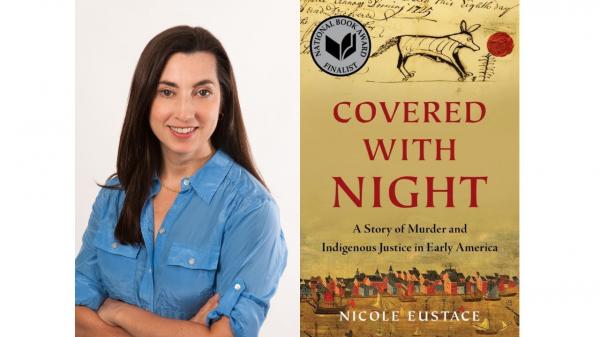

Here are a few excerpts from a book I recently read, "Covered with Night: A Story of Murder and Indigenous Justice in Early America," by Nicole Eustace.

The mayor and the members of the Philadelphia City Council are not even sure whether any roads exist at all west of the Schuylkill. Planners hope that someday Philadelphia will be an expansive city that spans the distance between two rivers, from the Delaware to the Schuylkill. But as of 1722, Philadelphia’s buildings have spread only a few blocks west from the Delaware. Despite the grand backwoods designs of a few would-be estate owners like William Keith, most Philadelphians have never so much as ventured over the Schuylkill. More and more traders and travelers from the west are crossing the Schuylkill at the point of High Street, then walking down its two-mile length to reach the city’s market. Yet few city dwellers travel in the reverse direction.

Mineral dreams fire the ambitions of many a European setting out for North America. The Spanish empire has reaped unimaginable wealth in gold and silver in its territories to the south, leaving the late-arriving English and French in desperate hopes of reproducing Spanish success. Books about the Americas routinely promise readers that the lands practically burst with bullion. A guidebook called the Atlas Geographicus, published in London in 1711, insists that, in Pennsylvania in particular, “the soil abounds with Mines, Samples of most sorts of Oar have been taken up here almost everywhere.” If this book does not explicitly promise precious metal, it certainly implies that colonial Pennsylvanians have the right to hope for mineral riches. Indeed, in this age of alchemy, many educated men believe that, in the right conditions, the skillful can transform even iron pyrite into gold.

But Peter Bezaillion, like all colonists dazzled by their own imaginations, stumbled over an inconvenient fact. Only extensive knowledge of the local land could yield clues about where to search for precious soil. And so, as they set out “in search of some Mineral or Ore,” Bezaillion and his French associates “pretended that in the Governor’s name they . . . required the Indians of Conestoga to send some of their People with them to assist them, and be serviceable to them, for which the Governor would pay them.” In the eyes of the members of the Provincial Council, Bezaillion practiced a double deception here, prospecting on land that belonged to the proprietors while trying to trick Indians into aiding him—all on the pretext that his efforts came at the behest of English authorities.

When Pennsylvania colonists continue to grumble about Native demands for “presents,” sometimes going so far as to mistake wampum simply as a Native form of money, they entirely miss the central importance of presence in the Native world. Wampum holds memories and messages more effectively than paper and parchment for the simple reason that it acquires full meaning only when held aloft in the hands of knowledgeable speakers. So much of colonial life relies on anonymous exchanges, from printed texts that circulate without authors ever meeting readers to manufactured products bought by consumers who never meet the producers. Knowledge grows and markets multiply in the colonists’ mobile transatlantic world, but personal relationships and communal responsibilities are being lost along the way. For Captain Smith, who has devoted himself to learning the languages that allow him to draw people together, plotting a journey without planning words of condolence and preparing belts of wampum would be obvious folly. Yet Governor Keith has hardly a glimmer of true understanding of Native ways.

Magic and science, wonder and terror, hope and fear. Settler colonists can never decide if they are on the verge of finding a new Eden—a place where wealth comes almost without toil and all the lush country is theirs for the taking—or if they have ventured to the very gates of hell, to a land where labor is forced by lash and land is seized by musket, where each person has a price and the cost of success is the surrender of every Christian ideal.

For all the fine talk you hear over cups and tankards at coffeeshops and tavern counters—gossip about fortunes in golden wheat or in mineral ore—much of the wealth being built by colonists in this new country comes from keeping iron control over flesh and bone.

Comments