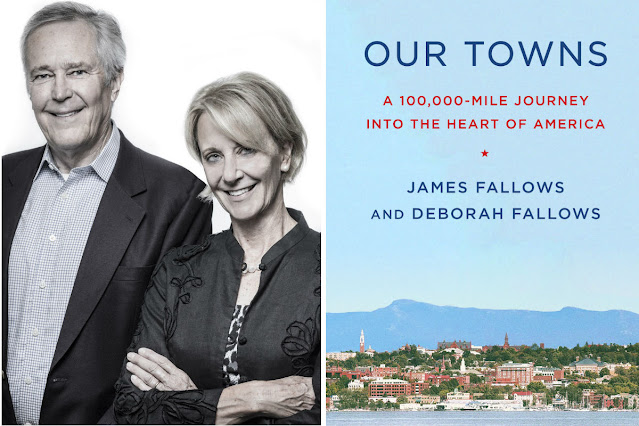

Here are a few excerpts from a book I recently read, "Our Towns: A 100,000-Mile Journey into the Heart of America," by Deborah and James Fallows.

By the end of the journey, we felt sure of something we had suspected at the beginning: an important part of the face of modern America has slipped from people’s view, in a way that makes a big and destructive difference in the country’s public and economic life. Despite the economic crises of the preceding decade and the social tensions of which every American is aware, most parts of the United States that we visited have been doing better, in most ways, than most Americans realize. Because many people don’t know that, they’re inclined to view any local problems as symptoms of wider disasters, and to dismiss local successes as fortunate anomalies. They feel even angrier about the country’s challenges than they should, and more fatalistic about the prospects of dealing with them.

We wanted to look at parts of the country generally missed by the media spotlight. That would mean reporting in the places often considered as “flyover country.” Such cities, medium-sized or below, and rural areas usually made their way to national attention only after a tornado or a mass shooting; during presidential-campaign season; or as backdrops for “concept” pieces like “The Private Prison Revolution” or “After Coal: What?” We were interested in places that had faced adversity of some sort, from crop failure to job loss to political crisis, and had looked for ways to respond.

When Whittenberg was preparing to open, in 2010, few people had gotten wind of it. High schoolers were hired to canvass the school’s neighborhood, introducing the school to parents and encouraging them to enroll their youngsters. By the second year, word was out, and out-of-district parents camped in front of the school for a week before registration, hoping to secure a first-come, first-served spot. The demand was so high that the local Lowe’s home store offered discounts on camping supplies. Registration day spun out of control. Videos showed parents stampeding the doors when they opened. The next year, the school switched to a lottery system. Now, a Whittenberg administrator told me, Greenville real estate agents advertise the location as a plus for houses listed in the Whittenberg district.

McClure says that cooperation and support happen naturally in the fashion industry in Columbus. Big brands, the likes of Abercrombie & Fitch, Designer Shoe Warehouse, Victoria’s Secret, Lane Bryant, and others, get along with the little start-ups and boutiques, he explained, and operate as though there is room for all to work for the greater good of fashion in Columbus. Several times, we heard the mantra that Columbus is No. 3 in fashion design after New York and Los Angeles.

Whether they come out and say it or not, many of the country’s most ambitious people assume that work of a certain level requires being in a certain place. This idea of a vast national sorting system for talent has huge ramifications. They range from politics to the distortion of real estate prices in a handful of coastal big cities. But as we continued to find, in countless other places across the country, people don’t have to start out assuming that most of what they take home will immediately go out for the rent or mortgage. That is because they have calculated that—in Duluth and Greenville and Redlands and Holland and Sioux Falls and Burlington and Allentown and even larger places like Columbus, Ohio, and Charleston—they can build their company, pursue their ambition, and realize their dream without crowding into the biggest cities.

Some people have always preferred the small-town life; of course, America has always had diverse regional centers; and, of course, locational concentration matters in many industries. I had known that before we started these travels. What I hadn’t known is how consistently, and across such a wide range, we would find people pursuing first-tier ambitions in what big-city people would consider the sticks.

Practicality: “It’s one of those places that has never had a boom, so booms and busts are relative. If you’re never up, you can’t be down.”

Lack of pretension: “Lots of people can make an album in the studio who can’t do it live.” (Mountain Stage is recorded before a live audience.) “That is very West Virginia, too: to deliver in person. We have hillbillies, but we’ll tell you what a hillbilly is—you [outsiders] don’t tell us.” This was two years before J. D. Vance’s book Hillbilly Elegy made the term a staple of political conversation. “A hillbilly isn’t an ignorant fool. He’s a straightforward, self-effacing, ‘what you see is what you get’ person. He relies on his friends because he doesn’t trust a lot of other things. He is not necessarily formally educated. But he is smart.”

Generosity: “If your car gets broken down, you want it to happen in West Virginia. This whole stuff about Deliverance, it’s just the opposite. If something happens, you want it to happen here. People will stop and help.” Groce told the story of a national network correspondent who came to interview people nearby and found them unwilling to answer questions. So he put up the hood of his car as if he were having engine trouble, and people came over to help him out and talk with him.

And once more from Jake Soberal: “What’s the main thing making Fresno better? I believe that we have a generation of young people who do not want to adopt their parents’ view of this place. Or the world’s view. That is really, really significant. Increasingly we’re able to count among those young people some of our most talented. Whereas before Fresno was famous for losing those people.”

Soberal said that a number of local groups were interested in changing the prevailing views of the city, from the mayor to the downtown alliance. He supports those efforts, he said. “But the group of people involved in changing what others think about the city is smaller than the group of people who say, ‘I don’t care what you, Dad, might think about Fresno. There is real data that makes me excited about what I can do here.’ That group is growing quite large, and the decisions they make are driven by data. They think, I can open a restaurant here, I can get a house here, I can build a company here. I don’t care that you think Fresno sucks.”

The ecological story behind the American Prairie Reserve was a scientific determination, around the year 2000, that there were only four extensive-grassland areas in the world that had never been plowed or reaped by mechanical harvester and thus, in principle, might have their original plant and animal ecosystems restored. One was in Kazakhstan, another in Patagonia, and a third in Mongolia—and all three of those were shrinking, as farming intruded on their borders. The fourth was in Montana, in the central region of the state, due north of Yellowstone Park in Wyoming, and was more intact than any of the others.

No comments:

Post a Comment