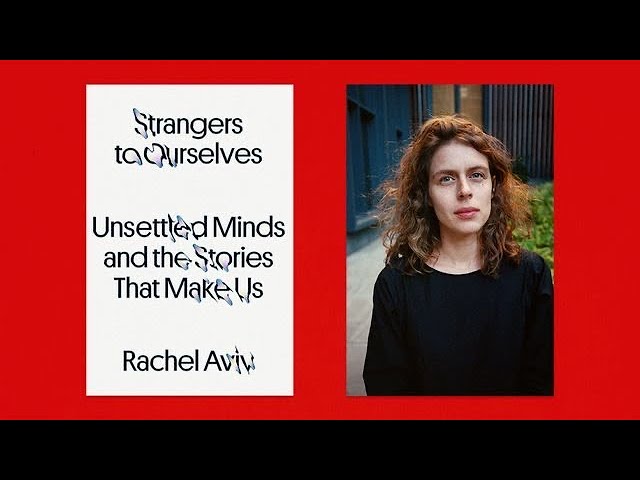

Here are a few excerpts from a book I recently read, "Strangers to Ourselves Unsettled Minds and the Stories That Make Us," by Rachel Aviv.

Julia asked the Lodge psychiatrists to give her son antidepressants. But at the time, the use of antidepressants was still so new that the premise of this form of treatment—to be cured without insight into what had gone wrong—seemed counterintuitive, even cheap. Drugs “might bring about some symptomatic relief,” Ross, Ray’s psychiatrist, acknowledged, “but it isn’t going to be anything solid in which he can say, ‘Hey, I’m a better man. I can tolerate feelings.’”

The antipsychotic Thorazine had been developed a few years earlier, in a lab in France, and for the first time many psychiatrists were confronting the possibility that people didn’t have to understand their childhood conflicts to get well. But the view was still unpopular. Kline said colleagues took him aside to warn him that, by claiming a drug could relieve depression, he was risking humiliation. “There was a large and adamant body of theoretical opinion that held that such a drug simply could not exist,” Kline wrote. The neuroscientist Solomon Snyder has written that, at the time, a psychiatrist engaged in biological research was “regarded as somewhat peculiar, perhaps suffering from emotional conflicts that made him or her avoid confronting ‘real feelings.’”

But Kline presented a new story about what sorts of feelings were “real.” One of the epigraphs to his book was a quote by Epictetus: “For you were not born to be depressed and unhappy.” When Kline tried iproniazid himself, he found that the drug produced a uniquely American kind of transcendence: he could work harder, faster, and longer.

In Hope Draped in Black, the scholar Joseph R. Winters revisits Freud’s “Mourning and Melancholia” to describe what happens when Black people realize that an ideal, like freedom or equality, has been withheld from them. The loss becomes internalized, undermining “any notion of self-coherence,” Winters writes. “Melancholy registers the experience of being rendered invisible, of being both assimilated into and excluded from the social order.” Barred from full recognition, the grief never resolves. “That’s what makes it all so hysterical, so unwieldy and so completely irretrievable,” James Baldwin said, using a similar image to evoke this unnamed loss. “It is as though some great, great, great wound is in the whole body, and no one dares to operate: to close it, to examine it, to stitch it.”

Helena Hansen, the psychiatrist and anthropologist at UCLA, said she’s found that Black patients tend to be less responsive to the idea that “your biology is deficient and you can fix that with technology,” a framework that was designed in part to reduce stigma. “When it comes to affluent white patients you can take care of moral blame using a biological explanation,” she said. These families often feel freed by the idea that an illness is no one’s fault. “But when it comes to Black and brown and poor patients, that same biological explanation is used to deflect blame away from the societal forces that brought them where they are. Because there is moral blame: the blame of having disinvested in people’s communities by doing things like taking away affordable housing or protection for workers.” She said that her patients have found it therapeutic and empowering when she acknowledges the societal structures that have contributed to their state of mind.

No comments:

Post a Comment