Too Short for a Blog Post, Too Long for a Tweet 380

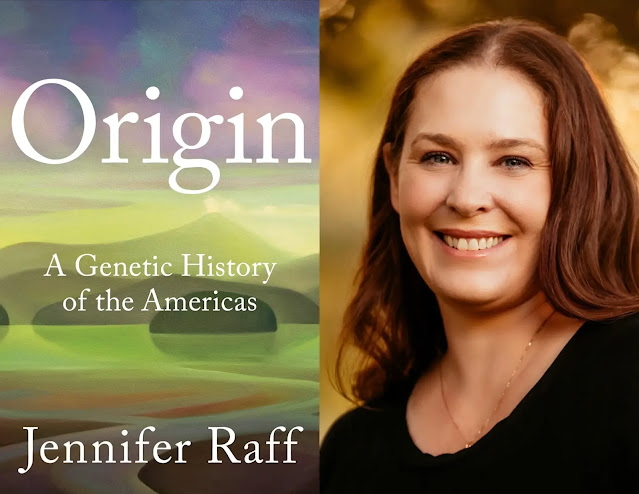

Here are a few excerpts from a book I recently read, "Origin: A Genetic History of the Americas," by Jennifer Raff.

The initial reaction from the communities was mixed.

Some were reluctant to disturb the human bones any further. But other

community members wanted to learn what information the ancient man could

reveal about the history of the people in the region. “As I remember

those initial talks,” Terry Fifield told me in an email, “council

members wondered who this person might be, whether he was related to

them, how he might have lived. It was that curiosity about the man that

inspired the partnership at the beginning.”

After

much discussion and debate, community members eventually agreed that

the scientists could continue their dig and study the ancient remains.

They stipulated that excavations would immediately cease if the cave

turned out to be a sacred burial site. They also mandated that the

scientists were to share their findings with them before they were

published and consult with community leaders on all steps taken during

the research—and the community members would rebury their ancestor

following the work.

So

while this book is about how scientific understandings of the origins

of Native Americans have changed, we cannot tell that story without also

scrutinizing how scientists have arrived at these understandings. This

is not a pleasant history to recount. The Indigenous inhabitants of the

Americas have been treated with disrespect, condescension, and outright

brutality by a number of scientists who have benefitted at the expense

of the people they were so curious about. This is the legacy that

contemporary anthropologists, archaeologists, and geneticists need to

confront head-on; there can be no honest progress in the scientific

study of the past without acknowledging those threads of human history

we have dismissed, neglected, or erased in the past. The journey to

knowledge has to involve self-scrutiny; scientific progress cannot be

divorced from the social context in which it takes place.

It

had become evident to physical anthropologists of the early 20th

century that the scenario that José de Acosta had originally proposed on

the basis of biblically inspired logic in the 16th century was, in

fact, supported by multiple lines of biological evidence.

But

evidence kept appearing that didn’t quite work with the model. Even as

better dating methods pinpointed the earliest appearance at Clovis to

13,200 years ago, the Clovis First model still couldn’t quite satisfy

everyone. From time to time, a maverick archaeologist would come forward

to present a site that didn’t fit the model; evidence that showed

people were present in the Americas before Clovis. These supposed

pre-Clovis sites irritated most senior archaeologists, who, like my

professor, already knew how the Americas were peopled. Like annoying

pebbles working their way into the shoes of a runner, the archaeologists

had to keep stopping to clear away these distractions before they could

make progress on their research. My generation of students was

inculcated with the belief that every single site proposed to predate

Clovis had one or more fatal flaws. The attitude at the time, one of my

colleagues told me, was basically “We know the answer. Don’t bother us

with data.”

In

return for your respect, caves offer you the unique experience of

seeing unparalleled treasures of nature: speleothems of the most

astonishing beauty created over thousands of years by what began as a

tiny accretion of minerals in water droplets. You have to move with

utmost care to avoid touching them as you scramble over rocks or crawl

through tunnels. Since your light source is usually a focused beam from a

headlamp or flashlight, you learn to maintain a constant state of

alertness in the underground world. As a child (and later as a teenager)

I loved feeling this single-minded focus for hours, listening to the

small sounds of water, our own footfalls, and the occasional flutter of

bat wings, and glimpsing something ancient and beautiful in the beam of

my flashlight every time I turned a corner.

Entering

a sacred burial space like Actun Tunichil Muknaliii requires an

additional level of respect: for the place itself, for its history, for

the ancestors interred there, and for the living people who still

consider it sacred. It’s an important consideration when visiting such

places as tourists; one must be mindful of how the vocabulary of

“discovery” and “adventure” and the opportunity to gawk at the remains

of ancient peoples may be demeaning to them and harmful to their

descendants.

One

possible refuge for humans during the bitterly cold Ice Age was the

southern portion of central Beringia—a region that is presently under

about 164 feet of ocean but would have been lowland coastline 50,000 to

11,000 years ago. Unlike the steppe-tundra regions, the southern coast

of the land bridge would have been much warmer and wetter because of its

proximity to the ocean.

Paleoenvironmental

evidence shows that it actually contained wetlands, with peat bogs and

trees like spruce, birch, and adler that people could have burned for

fuel. Waterfowl would have visited this place, and they and other

animals would have provided a reliable supply of food for the

Beringians. This model for Native American origins explains the genetic

evidence of isolation. To some archaeologists, it also meshes well with

the archaeological evidence. Beringians living on the south coast of the

land bridge had access to Pacific marine resources, including kelp,

shellfish, fish, and marine mammals. A prolonged stay in a coastal

region would have required the population to develop adaptations for

these new resources. If true, this period of isolation meant that the

First Peoples already had the culture and knowledge needed for thriving

in coastal environments by the time routes into the Americas became

accessible a few thousand years later. It means that Beringia should

more properly be viewed as a lost continent than as a land bridge. The

term land bridge gives the impression that people raced across a narrow

isthmus to reach Alaska. The oceanographic data clearly show that during

the LGM, the land bridge was twice the size of Texas. If the Out of

Beringia model is correct, Beringia wasn’t a crossing point, but a

homeland, a place where people lived for many generations, sheltering

from an inhospitable climate and slowly evolving the genetic variation

unique to their Native American descendants.

Comments