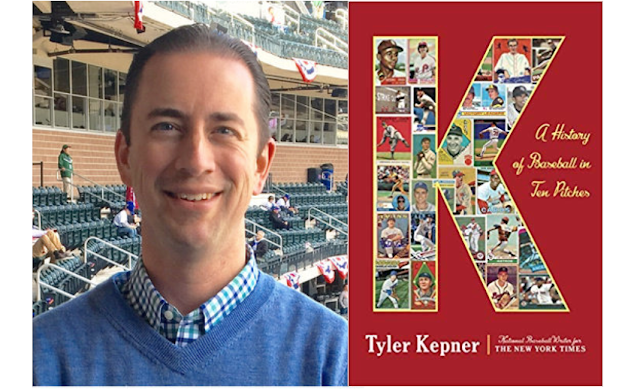

Here are a few excerpts from a book I recently read, "K: A History of Baseball in Ten Pitches," by Tyler Kepner.

Batters hit just .233 in at-bats ending with sliders in 2017, their worst average against any pitch. The Pirates’ Chris Archer, who has one of baseball’s best sliders, gave a simple reason why: “Of all the true breaking balls—slurve, curve, slider—it looks the most like a fastball for the longest.”

Traded to the Dodgers, Hill sliced curveballs through the National League, ending with six shutout innings against the Cubs in the playoffs. That December, the Dodgers brought him back with a three-year, $48 million contract—a jackpot, at last, after 15 pro seasons, a deal that would soon lead Hill to the World Series. He wept at the news conference announcing it.

“I think that’s life, right?” Hill said, reflecting on the rocky path brought to riches by perseverance and a killer curve. “You’re going to be thrown a lot of different curveballs.”

The weird pitch that hurts the elbow. In the graveyard of baseball, those words could be etched on the tombstone of the screwball, a pitch that once brought glory to so many. The fadeaway, it turns out, was the right name all along.

The ethics of spitters and scuffed balls offer a window to a kind of logic that seems convoluted, yet makes perfect sense to many in the game. To Keith Hernandez, whose Mets were flummoxed in the 1986 playoffs by Houston’s Mike Scott, the method of subterfuge is everything: do something illicit away from the field—corking a bat, injecting steroids—and that’s cheating. Do something on the field, in front of everyone, and get away with it? As Hernandez wrote in his book, Pure Baseball: “More power to you.”

No comments:

Post a Comment