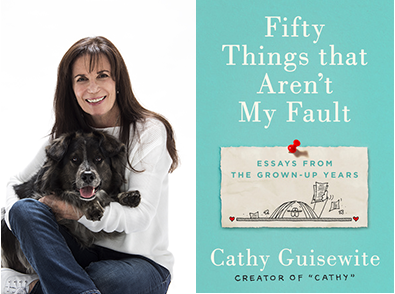

Here are a few excerpts from a book I recently read, "Fifty Things That Aren't My Fault: Essays from the Grown-up Years," by Cathy Guisewite.

“Hey, Mom.” That’s all she had to say. I’m a mom-linguist at this point—can translate four hundred slightly different inflections of “Hey” and “Mom” into four hundred completely different meanings.

"I’ll book you a flight home,” I answered warmly, and heard many, many words of relief in her “Okay.”

“A birth mother came in today who’d like to meet you.”

“What?” I choked back. I was single and terrified. I’d only signed up with an adoption facilitator a couple of months earlier and was still wrestling with whether I could or should really do this on my own.

Suddenly there I was, twenty-four hours later, with my hand touching the rest of my life through the shirt of an equally scared, unbelievably trusting stranger. In one day I’d gone from the dream of having a daughter “someday” to being half of a miraculous meeting of two moms—one who was bringing a little girl into the world; one who would take her through it.

I would say it isn’t possible to describe the bond that grew between my daughter’s birth mother and me in the four weeks that followed, except it felt to me, and I’m pretty sure to her too, that our bond was deep and immediate the minute we met. I will never be able to comprehend the selflessness of her love that made it possible for her to seek a life for her child she knew she couldn’t provide. I can still hardly breathe when I think of the faith she put in me to be the mom she couldn’t be. I drove my daughter’s birth mother to the hospital when she went into labor. The admitting nurse asked if we were sisters. So much more than that, I’ve thought a million times since that night. We are so very much more than that.

I held her birth mother’s hand while our daughter was being born. I fed the baby that suddenly belonged to both of us tiny bottles in the hospital nursery day and night until she was ready to come home. I made sure our daughter and her birth mother had time alone together in the hospital, and that the three of us had a little time together, too. Then I drove our daughter home by myself, just the two of us. I was so overwhelmed by the impossibly complicated emotion of driving her away from her birth mother, the incomprehensible joy and responsibility of becoming her life mother, that I couldn’t stand to have anyone else in the car. I was on my own and thousands of miles away from any family. My daughter and I locked around each other deeply and completely, and have been each other’s world ever since.

I look at her now, engrossed in her iPhone with the two thousand Facebook friends she’d rather be with than me. I would do anything for my child. I would crawl across the earth on my hands and knees to help her. I would die for her. I would give her anything—my food, my blankets, my bed, my air, my home, my life. She is my life. I would do anything for her.

Anything, it turns out, except keep my mouth shut.

“Pull your shoulders back, honey. You’re all slumpy.” I’ve lost all ability to screen outgoing messages. I continue . . .

I walk down the hall to the home office Dad shares with Mom. Command Central for all the critical business of their days. It’s half the size of a spare bedroom, with two desks, two swivel chairs, two file cabinets, two computers (one desktop, one laptop), reams of paper, multipacks of tape, staples, pencils, file folders, and many “pending” piles. A room so full of meticulous records from the past and supplies for the future that if one parent’s sitting at one desk and the other wants to get to the other desk, they both have to stand and sort of twirl around for the second person to squeeze through. The dance they’ve done a million times in their sixty-five-year marriage. The dance I would have done with my husband a maximum of two times before renting office space across town.

My daughter is friends with a universe of strangers, people she’s never met in countries she’s never been to: great big global groups of Facebookers, bloggers, and gamers. Attachments are fragile and fickle, and all in the air. Landlines don’t exist. Single-tasking is ancient history. Human contact is to be avoided whenever humanly possible.

Mom and Dad make weekly pilgrimages to the bank to visit the people guarding their money. They know their bank tellers’ names and wedding anniversaries and how it’s going with the recent foot surgery. My daughter never goes inside a bank. Has never even spoken to a drive-up teller. Money comes out of an ATM on the sidewalk; money goes in by snapping photos of birthday checks on the kitchen counter and clicking deposit.

Mom and Dad shop in stores, eat in restaurants, and buy tickets for upcoming plays and ballets at the theater box office in person. Dad doesn’t even like to drop mail in the mailbox that’s in front of the post office. He likes to park, go inside, and hand his letters right to a U.S. Postal Worker he knows by name.

My daughter shops, returns, buys tickets, pays bills, and orders takeout online. She scans and bags her own groceries in the self-check-out area at the supermarket. She’s been in a post office once, when I tried to force her to learn how to buy stamps for the thank-you notes I forced her to write by hand. Never even made it to the counter. “They have machines, Mom!” She pointed and, before I could stop her, ran to the self-serve machine in the lobby and came back waving a sheet of generic metered first-class postage stamps over her head like a millennial victory flag.

“But you can pick out pretty stamps at the counter!” I implored, trying to pull her toward the long line of people my age and older who were waiting for a person to wait on them. “The postal worker can show you all the pretty stamps and you can pick the ones that match the sentiment of the notes you’re sending!” My daughter looked at me with the same sick disbelief as the day the credit card reader wasn’t working on the gas pump where she stood trying to fill the tank of her car.

“The credit card thing isn’t working on the gas pump!” she wailed through the window of the passenger seat where I sat.

“Walk inside the gas station and give your card to the person behind the counter,” I answered as patiently as I could.

“WHAT?!” she recoiled.

“There’s a person inside! Give your credit card to the person!” I said less patiently.

“WHAT?! I’m not dealing with some random dude!” She got back in the car, slammed the door, and started the engine. “I’ll drive to a different station where things work! Seriously, Mom? The person??!”

Mom and Dad are brick and mortar. Face-to-face. Grounded. When Mom and Dad are with friends, no one’s twitching to check text messages or Instagrams. People are fully there when they’re there, plugged in to the moment and one another. Relationships are anchored, connected by all those visible and invisible cords. Is that why the friendships, marriages, and sort of everything else, including all the cars and appliances made by their generation, seemed to last a lot longer?

I think a little wistfully that the last cord that connected my daughter to something that really mattered was the umbilical one. What will keep the people in her world attached to each other or anything else when the people in my parents’ and my world are gone? I want my daughter to know the strength and clarity of not wandering that far from the base unit that’s helped make my parents’ relationships so solid and my life so secure. I want her to stay connected to the power source of principles, values, faith, and family that will help her be grounded and safe.

But I also want my parents to experience the thrill of unplugging. They might not ever be ready for the wonder of carrying the Encyclopedia Britannica in a smartphone in their pants pockets and aprons, but they could at least experience the freedom of taking a phone call on the front porch with the World Wide Web on their laps.

I want, for one minute of my life, to not feel right in the middle.

“How will you dial 911 if you’re unconscious?” I ask, my benevolent caregiver patience wearing thin.

They look at me as if I’m the illogical one.

“We’ll dial 911 before we become unconscious!” Dad exclaims. “Honestly, honey! You worry too much!”

They call it the “sandwich generation,” but it seems much more squashed than that. More like the “panini generation.” I feel absolutely flattened some days by the pressure to be everything to everyone, including myself.

“How about a used sticky note??” I ask, picking one off the counter and holding it in the air. “Can I throw out one used sticky note with a grocery list from last Thanksgiving?!”

“No! I wrote the Holecs’ new address on the back of that!” Mom says, plucking it from my hand.

“You use the backs of sticky notes??”

"You don’t use the backs of sticky notes??”

I spent nineteen years trying to expose my daughter to art, music, dance, theater, literature, and the wonders of nature. All those conversations in the botanical gardens, she’ll forget. All those concerts, gone. This, she’ll remember. The big takeaway from childhood: Mother can’t be in the house with an open container of Cool Whip.

She stares at me with critical college student eyes. I search them for a flicker of her five-year-old eyes—the ones that saw me as perfect, back when she wanted to be just like me. All I can find are the teen ones, recalculating my standing and reaffirming her superiority.

She shakes her head. “Wow.”

I’m not sure if it’s because of shame or surrender or just because this scene is so ridiculous, but her “Wow” makes me start laughing, which makes her start laughing. And then we’re laughing together, doubled over each other in the kitchen. I’m so far from being perfect, and she’s so close to needing me not to be perfect. There’s relief, I think, that the guard can finally be let down. If she can remember this moment—where her old vision of me and her new vision of me blur into some loving acceptance of Mom as an Actual Human—it’s surely more precious than anything they tried to teach her through the self-guided tour headset I forced her to wear at the Natural History Museum.

No comments:

Post a Comment