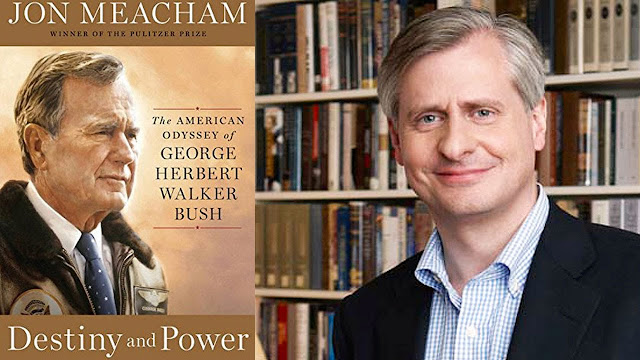

Here are a few excerpts from a book I recently read, "Destiny and Power: The American Odyssey of George Herbert Walker Bush," by Jon Meacham.

For all Bush knew Ronald Reagan could die on the operating table in the waning hours of afternoon. Yet the vice president showed no fear, no anxiety. “He seems so calm,” Jim Wright wrote in a diary he kept on the flight, “no signs whatever of nervous distress.” In a way, Bush had been here before. Long ago he had been charged with life-and-death responsibilities on an airborne mission. Then he had been twenty years old, an aviator in the vast mosaic of war. Now he was in middle age, a statesman returning to the precincts of temporal power. Then, amid fire and smoke, he had finished his mission. Now, amid uncertainty and doubt, he was determined to do his duty, which, as he saw it, was to lead quietly and with dignity.

Ed Pollard and John Matheny, the vice president’s air force aide, conferred with Bush about arrangements upon arrival in Washington. “There might be a crowd at Andrews,” Pollard said. “If you don’t mind, sir, we’d like to bring the plane into the hangar and disembark there.” Bush agreed. Then the conversation shifted to the next step of the journey. Pollard and Matheny argued that Bush should take a helicopter from Andrews directly to the South Lawn of the White House. That was by far the fastest route—faster and safer than helicoptering to Observatory Hill and driving down Massachusetts Avenue to the White House.

The idea made all the sense in the world—except to Bush. His first rule as vice president, he recalled, was the “most basic of all the rules....The country can only have one President at a time, and the Vice President is not the one.” A showboating vice president who attracted attention to himself was a reminder of the president’s absence.Intuitively, Bush believed that the stronger he looked the weaker the president might seem. “At this moment I am very concerned about the symbolism of the thing,” Bush said to Pollard and Matheny. “Think it through. Unless there’s a compelling security reason,I’d rather land at the Observatory or on the Ellipse.”

Landing on the South Lawn was the president’s prerogative, and the last thing Bush wanted was to be seen as trying to usurp the privileges of the president. The South Lawn felt “too self-important,” Untermeyer wrote of the debate between Bush and his security men. There was precedent, Pollard and Matheny countered, for a vice president to use the South Lawn. “But we have to think of other things,” Bush replied. “Mrs. Reagan, for example.”

Bush understood the logistical and symbolic arguments for the South Lawn. “By going straight to the White House, we’d get there in time for the 7 P.M. network news,” Bush recalled. “What better way was there to reassure the country and tell the world the executive branch was still operating than to show the Vice President, on live TV, arriving at the White House?” The prospect, however, troubled Bush. “The President in the hospital...Marine Two dropping out of the sky, blades whirring, the Vice President stepping off the helicopter to take charge,” Bush mused. “Good television, yes—but not the message I thought we needed to send to the country and the world.”

Matheny was thinking in practical terms. “We’ll be coming in at rush hour,” he told Bush. “Mass Avenue traffic will add anywhere from ten to fifteen minutes to your arrival time at the White House.”

“Maybe so,” Bush said, “but we’ll just have to do it that way.”

“Yes, sir,” Matheny said, but Bush saw that he looked puzzled.

“John,” Bush said, “only the President lands on the South Lawn.”

The assets that made

Bush an effective adviser to Reagan and might make him a sound

president—his aversion to sloganeering, his belief in bipartisanship,

his devotion to principled compromise—were, in his reading of the

Republican electorate of 1984, liabilities.

Bush was

already thinking about how to unify the party for the fall. The Dole

voters,he believed, would be on board: They were Republican regulars.

The Pat Robertson brigades struck Bush as more problematic—they seemed

more interested in ideology and theology than in political victory.

Campaigning in Kingsport, Tennessee—a thoroughly Republican city in a

state Reagan had carried twice—Bush encountered a stony-faced Robertson

backer who refused to shake the vice president’s hand.“Look, this is a

political campaign,” Bush said to her. “We’ll be together when it’s

over.” The woman was unmoved, and Bush, in the privacy of his diary,

reflected:

Still, this staring, glaring ugly—there’s something

terrible about those who carry it to extremes. They’re scary. They’re

there for spooky, extraordinary right-winged reasons. They don’t care

about Party. They don’t care about anything. They’re the excesses. They

could be Nazis, they could be Communists, they could be whatever. In

this case, they’re religious fanatics and they’re spooky. They will

destroy this party if they’re permitted to take over. There is not

enough of them, in my view, but this woman reminded me of my John Birch

days in Houston. The lights go out and they pass out the ugly

literature. Guilt by association. Nastiness. Ugliness.Believing the

Trilateral Commission, the conspiratorial theories. And I couldn’t

tell—it may not be fair to that one woman, but that’s the problem that

Robertson brings to bear on the agenda.

In the wake of Bush’s

win in New Hampshire, President Reagan finally allowed himself to be

more expansive about the Republican field. At lunch on the last day of

February 1988, Bush recalled, Reagan “made a comment that Dole is mean,

and shows a mean side....He didn’t think Kemp was presidential at all,

and he made a comment that he was concerned about Robertson and some of

the extremes that he brings into the party.” Another sign of Bush’s

success: a Kemp supporter called Jonathan Bush to say “Jack will get out

and endorse me if we’ll make a deal on the Vice Presidency.” It was the

latest in a series of feelers from Kemp about the second spot on a Bush

ticket. “I don’t know how we’re ever going to handle this, but I just

told them all—everybody—that there must be no indication of any deal of

any kind,” Bush dictated on Thursday, March 3. He wanted to keep his

options open. (Though not totally open: The New York developer Donald

Trump mentioned his availability as a vice presidential candidate to Lee

Atwater. Bush thought the overture “strange and unbelievable.”

No comments:

Post a Comment