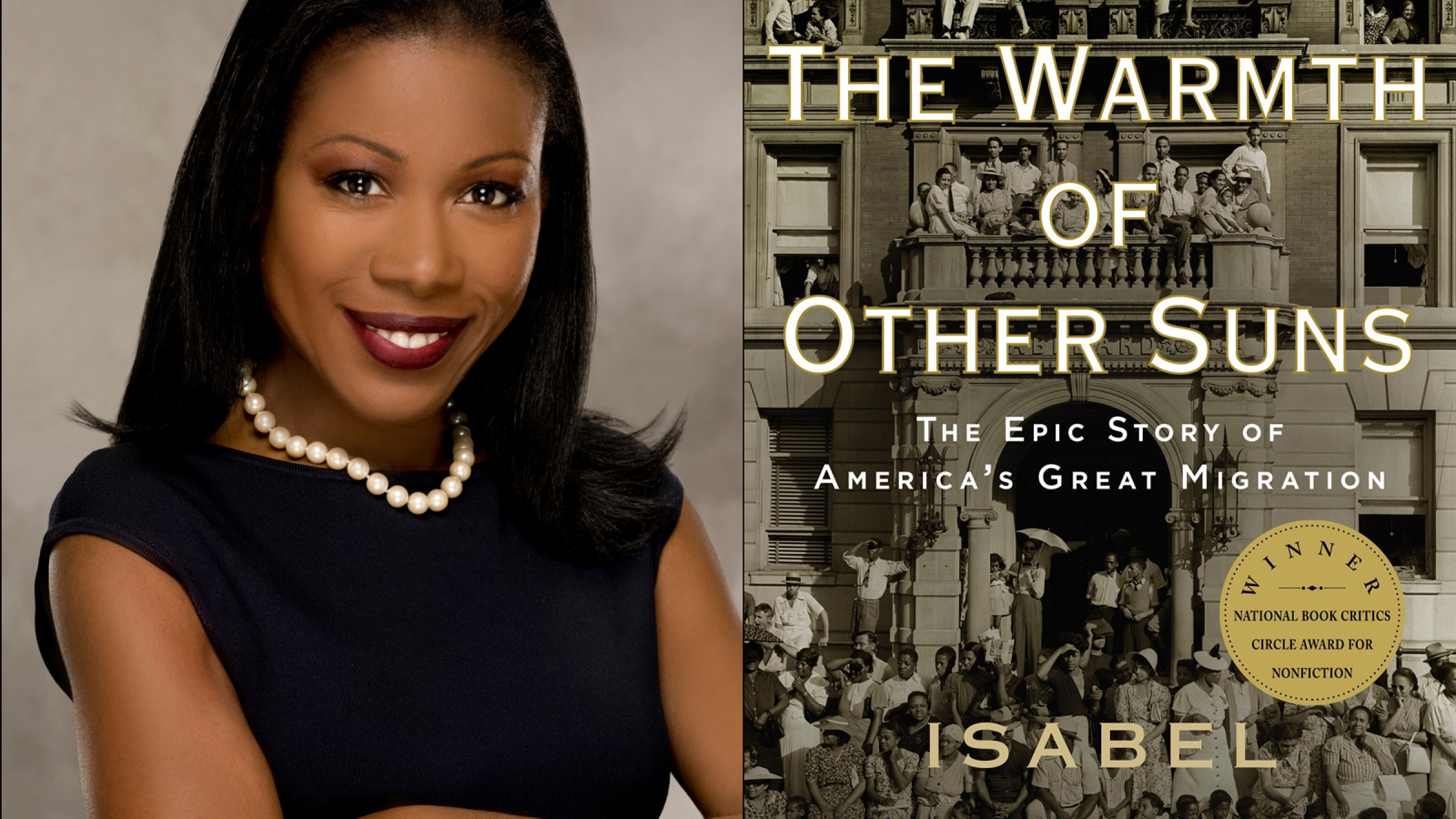

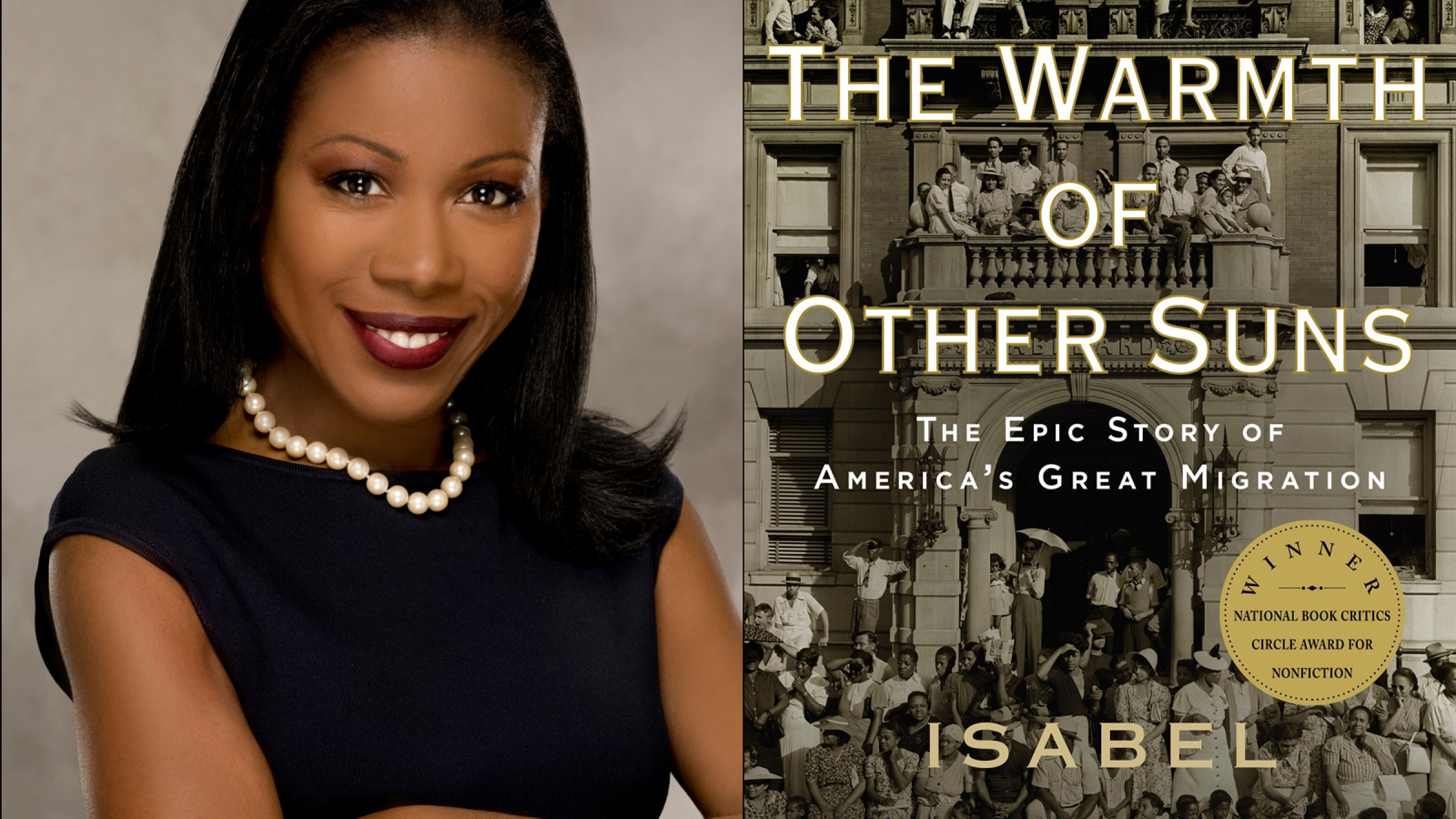

Here are a few excerpts from a book I recently read, "The Warmth of Other Suns The Epic Story of America's Great Migration," by Isabel Wilkerson.

Over the course of six decades, some six million black southerners left the land of their forefathers and fanned out across the country for an uncertain existence in nearly every other corner of America. The Great Migration would become a turning point in history. It would transform urban America and recast the social and political order of every city it touched. It would force the South to search its soul and finally to lay aside a feudal caste system. It grew out of the unmet promises made after the Civil War and, through the sheer weight of it, helped push the country toward the civil rights revolutions of the 1960s.

During this time, a good portion of all black Americans alive picked up and left the tobacco farms of Virginia, the rice plantations of South Carolina, cotton fields in east Texas and Mississippi, and the villages and backwoods of the remaining southern states—Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, North Carolina, Tennessee, and, by some measures, Oklahoma. They set out for cities they had whispered of among themselves or had seen in a mail-order catalogue. Some came straight from the field with their King James Bibles and old twelve-string guitars. Still more were townspeople looking to be their fuller selves, tradesmen following their customers, pastors trailing their flocks.

They would cross into alien lands with fast, new ways of speaking and carrying oneself and with hard-to-figure rules and laws. The New World held out higher wages but staggering rents that the people had to calculate like a foreign currency.

The places they went were big, frightening, and already crowded—New York, Detroit, Chicago, Los Angeles, Philadelphia, and smaller, equally foreign cities—Syracuse, Oakland, Milwaukee, Newark, Gary. Each turned into a “receiving station and port of refuge,” wrote the poet Carl Sandburg, then a Chicago newspaper reporter documenting the unfolding migration there. The people did not cross the turnstiles of customs at Ellis Island. They were already citizens. But where they came from, they were not treated as such. Their every step was controlled by the meticulous laws of Jim Crow, a nineteenth-century minstrel figure that would become shorthand for the violently enforced codes of the southern caste system. The Jim Crow regime persisted from the 1880s to the 1960s, some eighty years, the average life span of a fairly healthy man. It afflicted the lives of at least four generations and would not die without bloodshed, as the people who left the South foresaw.

Over time, this mass relocation would come to dwarf the California Gold Rush of the 1850s with its one hundred thousand participants and the Dust Bowl migration of some three hundred thousand people from Oklahoma and Arkansas to California in the 1930s. But more remarkably, it was the first mass act of independence by a people who were in bondage in this country for far longer than they have been free.

“The story of the Great Migration is among the most dramatic and compelling in all chapters of American history,” the Mississippi historian Neil McMillen wrote toward the end of the twentieth century. “So far reaching are its effects even now that we scarcely understand its meaning.” Its imprint is everywhere in urban life. The configuration of the cities as we know them, the social geography of black and white neighborhoods, the spread of the housing projects as well as the rise of a well-scrubbed black middle class, along with the alternating waves of white flight and suburbanization—all of these grew, directly or indirectly, from the response of everyone touched by the Great Migration. So, too, rose the language and music of urban America that sprang from the blues that came with the migrants and dominates our airwaves to this day.

So, too, came the people who might not have existed, or become who they did, had there been no Great Migration. People as diverse as James Baldwin and Michelle Obama, Miles Davis and Toni Morrison, Spike Lee and Denzel Washington, and anonymous teachers, store clerks, steelworkers, and physicians, were all products of the Great Migration. They were all children whose life chances were altered because a parent or grandparent had made the hard decision to leave.

The Great Migration would not end until the 1970s, when the South began finally to change—the whites-only signs came down, the all-white schools opened up, and everyone could vote. By then nearly half of all black Americans—some forty-seven percent—would be living outside the South, compared to ten percent when the Migration began.

Before he begins his story, he tells you it’s a long one and you can’t get it all. He’s lived too many lives, done too much, known too many people, ridden so high and so low that there’s no point in fooling yourself into thinking you can capture the whole of it.

You could try, of course, and he agrees to give as much as he can.

“I love to talk,” he says, a smile forming on his still-chiseled face as he sits upright in his tulip chair. “And I am my favorite subject.”

Another boy from Monroe who migrated with his parents to Oakland took an entirely different path. He would go on to become one of the greatest basketball players of all time. Bill Russell was born in Monroe in 1934 and watched his parents suffer one indignity after another. His father once went to a gas station only to be told he would have to wait for the white people to get their gas first. He waited and waited, and, when his turn seemed never to come, he started to pull off. The owner came up, put a shotgun to his head, and told him he was not to leave until all the white people had been served.

“Boy, don’t you ever do what you just started to do,” the station owner said.

As for Russell’s mother, a policeman once grabbed her on the street and ordered her to go and take off the suit she was wearing. He said that she had no business dressing like a white woman and that he’d arrest her if he ever saw her like that again. Bill Russell watched his mother sit at the kitchen table in tears over the straits they were in.

Soon afterward, his parents packed up the family and moved to Oakland, where a colony of people from Monroe had fled. Russell was nine years old. He would get to go to better schools, win a scholarship to the University of San Francisco, and lead his team, the Dons, to two NCAA championships, a first for an integrated basketball team, collegiate or professional. He would join the Celtics in 1956 and lead Boston to eleven championships in his thirteen seasons. He would become perhaps the greatest defensive player in NBA history and the first black coach in the NBA. There is no way to know what might have happened to Bill Russell had his parents not migrated. What is known is that his family had few resources and that he would not have been allowed into any white college in Louisiana in the early 1950s, and thus would not have been in a position to be recruited to the NBA. The consequences of his absence from the game would now be unimaginable to followers of the sport.

In attending to the needs of his white clientele, he would be addressed as “boy,” as was the custom when he was working the white cars, even though by now he was twenty-seven years old and towered over most everyone who addressed him as such.

They could call him what they wanted on the train. He didn’t like it, but it didn’t define him. He lived in Harlem now and was free.

In the end, none of these things worked, not because anti-black forces gave up or grew more tolerant but because of the more fluid culture and economics of the North—the desire of whites to sell or rent to whomever they chose whether for profit or out of fear, necessity, or self-interest, or the temptation of higher rents that could be extracted from colored tenants with few other places to go.

Just as significantly, these things didn’t work because of what might be called the dispassion of the indifferent. The silent majority of whites could be frightened into lockstep solidarity in the authoritarian South but could not be controlled or willed into submission in the cacophonous big cities of the North.

This would suggest that the people of the Great Migration who ultimately made lives for themselves in the North and West were among the most determined of those in the South, among the most resilient of those who left, and among the most resourceful of blacks in the North, not unlike immigrant groups from other parts of the world who made a way for themselves in the big cities of the North and West.

There appeared to be an overarching phenomenon that sociologists call a “migrant advantage.” It is some internal resolve that perhaps exists in any immigrant compelled to leave one place for another. It made them “especially goal oriented, leading them to persist in their work and not be easily discouraged,” Long and Heltman of the Census Bureau wrote in a 1975 report.

A survey of new migrants during World War II found that an overwhelming majority of them looked up to the people who were there before them, admired them, and wanted to be as assured and sophisticated as they were. But a majority of the colored people already in the New World viewed the newcomers in a negative light and saw them as hindering opportunities for all of them.

It turned out that the old-timers were harder on the new people than most anyone else. “Well, their English was pretty bad,” a colored businessman said of the migrants who flooded Oakland and San Francisco in the forties, as if from a foreign country. To his way of looking at it, they needed eight or nine years “before they seemed to get Americanized.”

As the migrants arrived in the receiving stations of the North and West, the old-timers wrestled with what the influx meant for them, how it would affect the way others saw colored people, and how the flood of black southerners was a reminder of the Jim Crow world they all sought to escape. In the days before Emancipation, as long as slavery existed, no freed black was truly free. Now, as long as Jim Crow and the supremacy behind it existed, no blacks could ever be sure they were beyond its reach.

One day a white friend went up to a longtime Oakland resident named Eleanor Watkins to ask her what she thought about all the newcomers.

“Eleanor,” the woman said, “you colored people must be very disgusted with some of the people who have come here from the South and the way they act.”

“Well, Mrs. S.,” Eleanor Watkins replied. “Yes, some colored people are very disgusted, but as far as I’m concerned, the first thing I give them credit for is getting out of the situation they were in.… Maybe they don’t know how to dress or comb their hair or anything, but their children will and their children will.”

Contrary to conventional wisdom, the decline in property values and neighborhood prestige was a by-product of the fear and tension itself, sociologists found. The decline often began, they noted, in barely perceptible ways, before the first colored buyer moved in. The instability of a white neighborhood under pressure from the very possibility of integration put the neighborhood into a kind of real estate purgatory. It set off a downward cycle of anticipation, in which worried whites no longer bought homes in white neighborhoods that might one day attract colored residents even if none lived there at the time. Rents and purchase prices were dropped “in a futile attempt to attract white residents,” as Hirsch put it. With prices falling and the neighborhood’s future uncertain, lenders refused to grant mortgages or made them more difficult to obtain. Panicked whites sold at low prices to salvage what equity they had left, giving the homeowners who remained little incentive to invest any further to keep up or improve their properties.

Thus many white neighborhoods began declining before colored residents even arrived, Hirsch noted. There emerged a perfect storm of nervous owners, falling prices, vacancies unfillable with white tenants or buyers, and a market of colored buyers who may not have been able to afford the neighborhood at first but now could with prices within their reach. The arrival of colored home buyers was often the final verdict on a neighborhood’s falling property value rather than the cause of it. Many colored people, already facing wage disparities, either could not have afforded a neighborhood on the rise or would not have been granted mortgages except by lenders and sellers with their backs against the wall. It was the falling home values that made it possible for colored people to move in at all.

The dispossessed children of the Great Migration but, more notably, the lifelong black northerners broken by the big cities let out a fury that made a mockery of the free harbor the North was reputed to be. A presidential commission examining the disturbances found that more black northerners had been involved in the rioting than the people of the Great Migration, as had mistakenly been assumed. “About 74 percent of the rioters were brought up in the North,” wrote the authors of what would become known as the Kerner Report. “The typical rioter was a teenager or young adult, a lifelong resident of the city in which he rioted.” What the frustrated northerners “appeared to be seeking was fuller participation in the social order and the material benefits enjoyed by the majority of American citizens,” the commission found.

It was in 1954 that the Supreme Court ruled on Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, declaring segregated schools inherently unequal and therefore unconstitutional. In a subsequent ruling in 1955, the Court ordered school boards to eliminate segregation “with all deliberate speed.”

Much of the South translated that phrase loosely to mean whenever they got around to it, which meant a time frame closer to a decade than a semester. One county in Virginia—Prince Edward County—closed its entire school system for five years, from 1959 to 1964, rather than integrate. The state funneled money to private academies for white students. But black students were left on their own. They went to live with relatives elsewhere, studied in church basements, or forwent school altogether. County supervisors relented only after losing their case in the U.S. Supreme Court, choosing finally to reopen the schools rather than face imprisonment.

Ida Mae Gladney, Robert Foster, and George Starling each left different parts of the South during different decades for different reasons and with different outcomes. The three of them would find some measure of happiness, not because their children had been perfect, their own lives without heartache, or because the North had been particularly welcoming. In fact, not a single one of those things had turned out to be true.

There had been sickness, disappointment, premature and unexpected losses, and, among their children, more divorces than enduring marriages, but at least the children had tried. The three who had come out of the South were left widowed but solvent, and each found some measure of satisfaction because whatever had happened to them, however things had unfolded, it had been of their own choosing, and they could take comfort in that. They believed with all that was in them that they were better off for having made the Migration, that they may have made many mistakes in their lives, but leaving the South had not been one of them.

All told, perhaps the most significant measure of the Great Migration was the act of leaving itself, regardless of the individual outcome. Despite the private disappointments and triumphs of any individual migrant, the Migration, in some ways, was its own point. The achievement was in making the decision to be free and acting on that decision, wherever that journey led them.

“If all of their dream does not come true,” the Chicago Defender wrote at the start of the Great Migration, “enough will come to pass to justify their actions.”

Many black parents who left the South got the one thing they wanted just by leaving. Their children would have a chance to grow up free of Jim Crow and to be their fuller selves. It cannot be known what course the lives of people like Toni Morrison, James Baldwin, Diana Ross, Aretha Franklin, Michelle Obama, Jesse Owens, Joe Louis, Jackie Robinson, Serena and Venus Williams, Bill Cosby, Condoleezza Rice, Nat King Cole, Oprah Winfrey, Berry Gordy (who founded Motown and signed children of the Migration to sing for it), the astronaut Mae Jemison, the artist Romare Bearden, the performers Jimi Hendrix, Michael Jackson, Prince, Sean “P. Diddy” Combs, Whitney Houston, Mary J. Blige, Queen Latifah, the director Spike Lee, the playwright August Wilson, and countless others might have taken had their parents or grandparents not participated in the Great Migration and raised them in the North or West. All of them grew up to become among the best in their fields, changed them, really, and were among the first generation of blacks in this country to grow up free and unfettered because of the actions of their forebears. Millions of other children of the Migration grew up to lead productive, though anonymous, lives in quiet, everyday ways that few people will ever hear about.

Most of these children would attend better schools than those in the South and, as a whole, outperform their southern white counterparts and nearly match the scores of northern-born blacks within a few years of arrival. Studies conducted in the early 1930s found that, after four years in the North, the children of black migrants to New York were scoring nearly as well as northern-born blacks who were “almost exactly at the norm for white children,” wrote Otto Klineberg, a leading psychologist of the era at Columbia University.

“The evidence for an environmental effect is unmistakable,” he reported. He found that the longer the southern-born children were in the North, the higher they scored. The results “suggest that the New York environment is capable of raising the intellectual level of the Negro children to a point equal to that of the Whites.” Klineberg’s studies of the children of the Great Migration would later become the scientific foundation of the 1954 Supreme Court decision in the school desegregation case, Brown v. the Board of Education, a turning point in the drive toward equal rights in this country.

In the end, it could be said that the common denominator for leaving was the desire to be free, like the Declaration of Independence said, free to try out for most any job they pleased, play checkers with whomever they chose, sit where they wished on the streetcar, watch their children walk across a stage for the degree most of them didn’t have the chance to get. They left to pursue some version of happiness, whether they achieved it or not. It was a seemingly simple thing that the majority of Americans could take for granted but that the migrants and their forebears never had a right to in the world they had fled.

As with immigrant parents, a generational divide arose between the migrants and their children. The migrants couldn’t understand their impatient, northern-bred sons and daughters—why the children who had been spared the heartache of a racial caste system were not more grateful to have been delivered from the South. The children couldn’t relate to the stories of southern persecution when they were facing gangs and drive-by shootings, or, in the more elite circles, the embarrassment of southern parents with accents and peasant food when the children were trying to fit into the middle-class enclaves of the North.

And though this immigration theory may be structurally sound, with sociologists even calling them immigrants in the early years of the Migration, nearly every black migrant I interviewed vehemently resisted the immigrant label. They did not see themselves as immigrants under any circumstances, their behavior notwithstanding. The idea conjured up the deepest pains of centuries of rejection by their own country. They had been forced to become immigrants in their own land just to secure their freedom. But they were not immigrants and had never been actual immigrants. The South may have acted like a different country and been proud of it, but it was a part of the United States, and anyone born there was born an American.

Over the decades, perhaps the wrong questions have been asked about the Great Migration. Perhaps it is not a question of whether the migrants brought good or ill to the cities they fled to or were pushed or pulled to their destinations, but a question of how they summoned the courage to leave in the first place or how they found the will to press beyond the forces against them and the faith in a country that had rejected them for so long. By their actions, they did not dream the American Dream, they willed it into being by a definition of their own choosing. They did not ask to be accepted but declared themselves the Americans that perhaps few others recognized but that they had always been deep within their hearts.

Comments