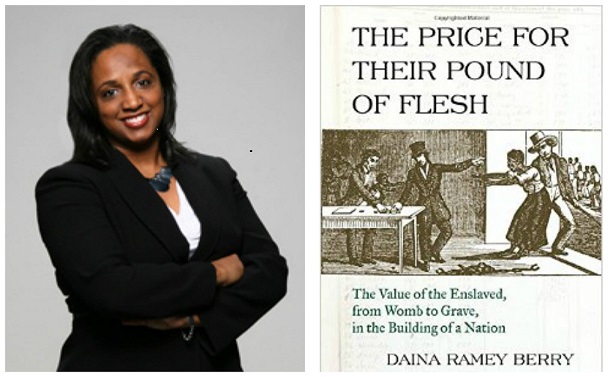

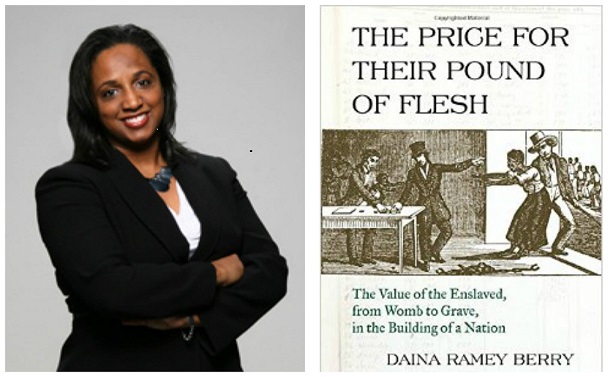

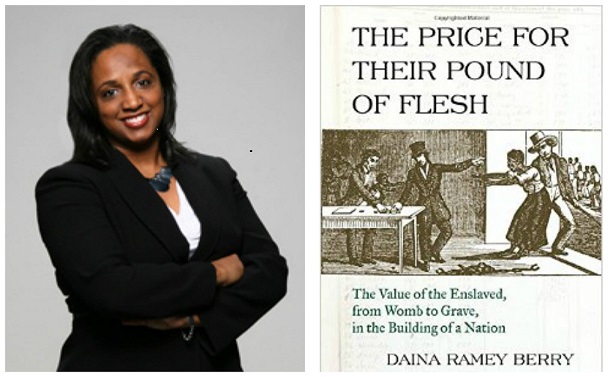

Here are a few excerpts from a book I recently read, "The Price for Their Pound of Flesh: The Value of the Enslaved, from Womb to Grave, in the Building of a Nation," by Daina Ramey Berry.

While I, and other scholars, contend that enslaved captives aboard slave ships in the Middle Passage had their personhood devalued, it is also true that their bodies, as commodities, increased in value over the course of their lives, reaching a peak in early adulthood. The tension between person and property merged in human chattel, and their awareness of their market value evolved as they matured.

Dave Harper and many other formerly enslaved people taught me about the valuation and devaluation that comes with blackness. “I was sold for $715,” he shared in a postslavery interview in the late 1930s. “When freedom come,” he said, “give me $715 and I’ll go back.”1 Harper and others knew that they were more valued in slavery than in freedom. Henry Banner noted, “I was sold for $2,300—more than I’m worth now.” Some scholars deliberately interpreted such reflections to mean that enslaved people preferred captivity to freedom. This bothered me. I couldn’t fathom why anyone would prefer captivity unless they did not value themselves. The many voices I encountered in the archives, as I wrote articles, books, and encyclopedias about gender and slavery, spoke to me loudly and clearly. Enslaved people, of course, preferred freedom.

Changes in the international slave trade and market innovations affected the domestic traffic in human beings. Given the markup for childbearing women, it appears that the acquisition of land and technological inventions altered the face of slavery at the turn of the century. Women played an important role, as the shift to import more enslaved women assured enslavers that they could produce additional labor sources on their farms and plantations. They did not have to depend on the market to purchase human property. Instead, by making calculated choices about their enslaved population, they could, in fact, grow their own. Enslaved women’s bodies were catalysts of nineteenth-century economic development, distinguishing US slavery from bondage in other parts of the world.

On a cold New York winter night, February 25, 1836, an audience of fifteen hundred people filled the City Saloon, anxiously anticipating the main attraction. Some had come from miles away and all had gladly paid the 50-cent admission fee for a show that promised to be like no other. Some arrived hoping to satisfy their long-held curiosity and wondered whether their theories would prove true. Others arrived not knowing what to expect. The saloon had been converted into a makeshift operating room for this special occasion, and the lights centered on a table in the middle of the stage.

The central figure in this drama, a deceased elderly enslaved woman named Joice Heth, lay atop the elevated table. She had died six days prior; her public autopsy was the main event that evening. The people surrounding her were Dr. David L. Rogers of Barclay Street Hospital, students, clergymen, New York Sun editor Richard Adams Locke, and lawyer Levi Lyman, who served as her “agent,” along with the infamous showman P. T. Barnum. Nearly everyone present was male, and some reports suggest that the entire procedure was distasteful, described as a “bloodily invasive circus.”

While still alive, Heth had spent her last year on tour, advertised as a purportedly 161-year-old enslaved woman and the former nurse of George Washington. Barnum made $1,500 per week displaying her at halls and facilities throughout the mid-Atlantic and Northeast. She told stories and sang hymns as part of Barnum’s “Freak Show.” In seven months, he made roughly $42,000 from this orchestrated public spectacle. In contemporary times, that would be equivalent to $1,102,336.5 As Barnum’s property, Heth made nothing. Now, less than a week after her death, Barnum organized his last show, a public autopsy to determine her cause of death and true age. People who paid to see her while living marveled at the old soul. Barnum claimed she had lived a century and a half, and although she was blind, she remembered seeing the Red Coats during the American Revolution.

No comments:

Post a Comment