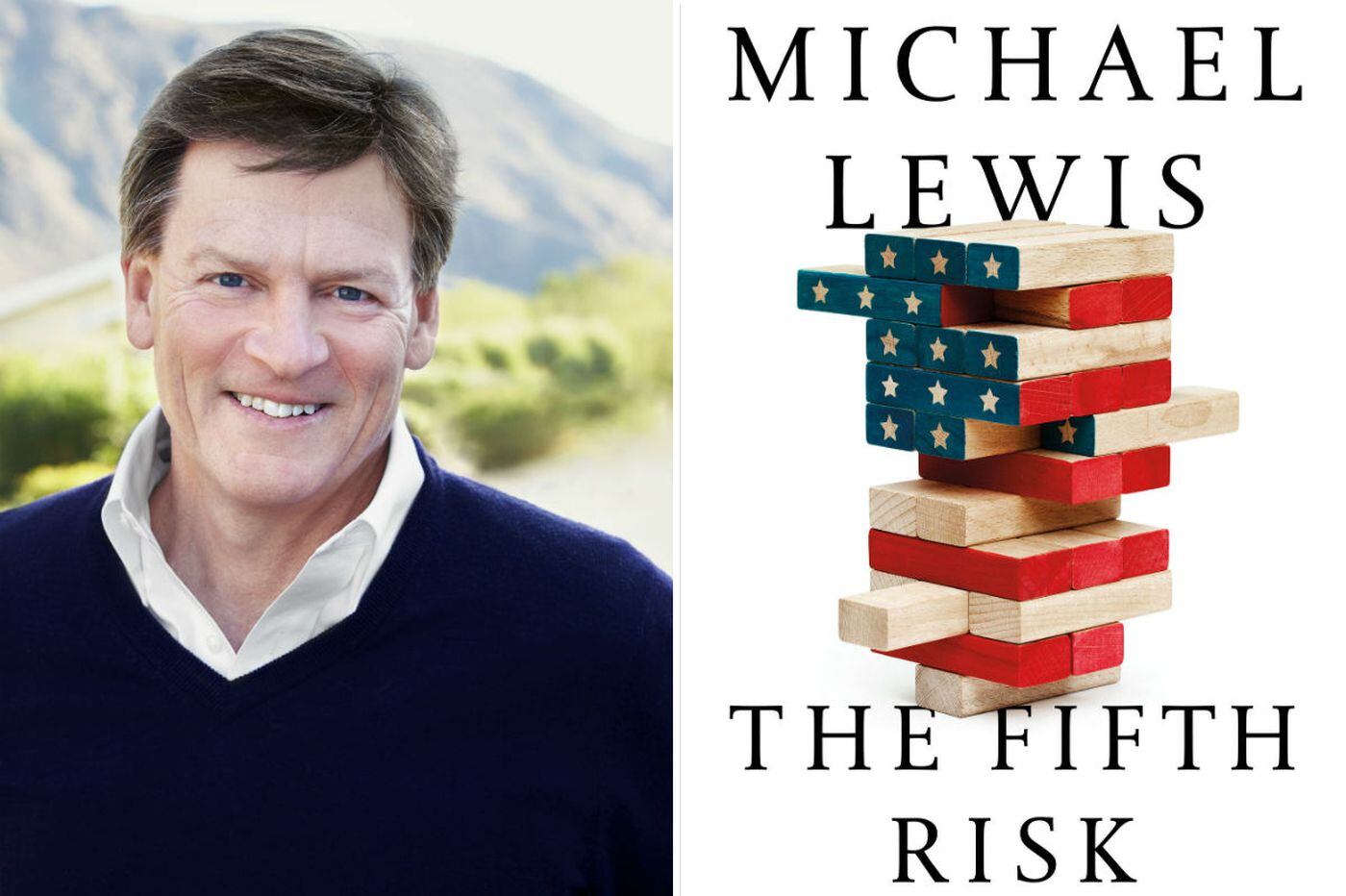

Here are a few excerpts from a book I recently read, "The Fifth Risk," by Michael Lewis.

Here are a few excerpts from a book I recently read, "The Fifth Risk," by Michael Lewis.There were hundreds of fantastically important success stories in the United States government. They just never got told. Max knew an astonishing number of them. He’d detected a pattern: a surprising number of the people responsible for them were first-generation Americans who had come from places without well-functioning governments. People who had lived without government were more likely to find meaning in it. On the other hand, people who had never experienced a collapsed state were slow to appreciate a state that had not yet collapsed. That was maybe Max’s biggest challenge: explaining the value of this enterprise at the center of a democratic society to people who either took it for granted or imagined it as a pernicious force in their lives over which they had no control. He’d explain that the federal government provided services that the private sector couldn’t or wouldn’t: medical care for veterans, air traffic control, national highways, food safety guidelines. He’d explain that the federal government was an engine of opportunity: millions of American children, for instance, would have found it even harder than they did to make the most of their lives without the basic nutrition supplied by the federal government. When all else failed, he’d explain the many places the U.S. government stood between Americans and the things that might kill them. “The basic role of government is to keep us safe,” he’d say.

There is another way to think of John MacWilliams’s fifth risk: the risk a society runs when it falls into the habit of responding to long-term risks with short-term solutions. “Program management” is not just program management. “Program management” is the existential threat that you never really even imagine as a risk. Some of the things any incoming president should worry about are fast-moving: pandemics, hurricanes, terrorist attacks. But most are not. Most are like bombs with very long fuses that, in the distant future, when the fuse reaches the bomb, might or might not explode. It is delaying repairs to a tunnel filled with lethal waste until, one day, it collapses. It is the aging workforce of the DOE—which is no longer attracting young people as it once did—that one day loses track of a nuclear bomb. It is the ceding of technical and scientific leadership to China. It is the innovation that never occurs, and the knowledge that is never created, because you have ceased to lay the groundwork for it. It is what you never learned that might have saved you.

Nobody understood what it did but, then, like so many United States government agencies, the Department of Commerce is seriously misnamed. It has almost nothing to do with commerce directly and is actually forbidden by law from engaging in business. But it runs the United States Census, the only real picture of who Americans are as a nation. It collects and makes sense of all the country’s economic statistics—without which the nation would have very little idea of how it was doing. Through the Patent and Trademark Office it tracks all the country’s inventions. It contains an obscure but wildly influential agency called the National Institute of Standards and Technology, stuffed with Nobel laureates, which does everything from setting the standards for construction materials to determining the definition of a “second” and of an “inch.” (It’s more complicated than you might think.) But of the roughly $9 billion spent each year by the Commerce Department, $5 billion goes to NOAA, and the bulk of that money is spent, one way or another, on figuring out the weather. Each and every day, NOAA collects twice as much data as is contained in the entire book collection of the Library of Congress. “Commerce is one of the most misunderstood jobs in the cabinet, because everyone thinks it works with business,” says Rebecca Blank, a former acting commerce secretary in the Obama administration and now chancellor of the University of Wisconsin. “It produces public goods that are of value to business, but that’s different. Every secretary who comes in thinks Commerce does trade. But trade is maybe ten percent of what Commerce does—if that.” The Department of Commerce should really be called the Department of Information. Or maybe the Department of Data.

No comments:

Post a Comment