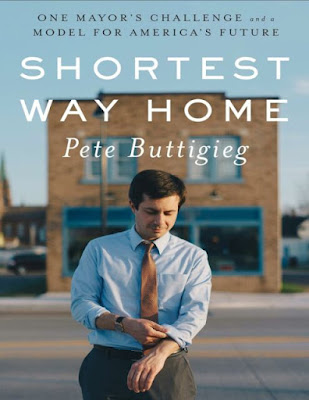

Here are a few excerpts from a book I recently read, "Shortest Way Home: One Mayor's Challenge and a Model for America's Future," by Pete Buttigieg.

Here are a few excerpts from a book I recently read, "Shortest Way Home: One Mayor's Challenge and a Model for America's Future," by Pete Buttigieg.

And, famously, there were the pocket watches. The South Bend Watch Company made products so precise that at trade shows they would freeze a watch in a big block of ice where you could see it still ticking faithfully inside. An old advertisement has an image of the watch in the ice, but for me the most remarkable thing in the ad is something else that strikes you as you read its big letters:

SOUTH BEND WATCH FROZEN IN ICE, KEEPS PERFECT TIME SOUTH BEND WATCH CO. SOUTH BEND, IND.

How powerful the very name of our city must have been. All you had to do to sell watches—besides put one in a block of ice—was name them after our city. That was enough, by way of branding: the name “South Bend” was a byword for workmanship and precision.

My room on the fourth floor was itself a wonder. It had hardwood floors and a wall of exposed brick, a style I’d only seen in fashionable restaurants and occasionally on television. There was even a fireplace (bricked up, but still), and a fire escape that, with some imagination and well-meaning disregard for rules, could serve as a balcony. A letter on your pillow had a list of everyone who had ever lived in your room, which in my case included Ulysses Grant Jr., Cornel West, and Horatio Alger.

IT WAS YEARS BEFORE I would get formal training in counterterrorism as a military officer, but it seemed clear even then as a history student that the new national approach on terrorism was likely to be self-defeating. The top priority of the terrorist—even more important than killing you—is to make himself your top priority. This is why protecting ourselves from terrorist violence is not enough to defeat terrorism, especially if we try to achieve safety in ways that elevate the importance of terrorists and wind up publicizing their causes. We all want to avoid being harmed—but if the cost of doing so is making the terrorist the thing you care about most, to the exclusion of the other things that matter in your society, then you have handed him exactly the kind of victory that makes terrorism such a frequent and successful tactic.

THE EXPERIENCE BROUGHT TO MIND a comment I had recently heard from former Baltimore Mayor and then-Governor Martin O’Malley about being a good mayor: that leaders make themselves vulnerable. It was an odd thing to hear from a mayor best known for data-driven performance management, not for emotional resonance. But that was precisely the point: using data in a transparent way exposes leaders to the vulnerability of letting people see them succeed or fail. Being vulnerable, in this sense, isn’t about displaying your emotional life. It has to do with attaching your reputation to a project when there is a risk of it failing publicly. The more a policy initiative resembles a performance where people are eager to see if the performer will succeed, the more vulnerable—and effective—an elected leader can be. The possibility of highly visible failure has an exceptional power to propel us to want to succeed, and that power can be harnessed to motivate a team or even a community to do something difficult.

It was through this effort that I began to understand the difference between my job and everyone else’s. The experts on the task force could evaluate the market conditions in the various neighborhoods and identify the legal tools for addressing neglected property. The council could allocate funds for dealing with the problem. The code enforcement staff could press landlords to address the condition of the houses. But only a mayor could furnish the political capital to get the project done, by publicly committing to a goal and owning the risk of missing it. I began to realize that the job was not about how much I knew, but how much I was willing to put on the line. The application of political capital, not necessarily any kind of personal expertise, was how I would earn my paycheck as a mayor.

Before going overseas, I had felt comfortable being more than one person, as we all sometimes must, according to the roles we are called to play. I knew how to toggle between mayor mode, officer mode, friend mode, and so on. But something about exposure to danger impresses upon you that a life is not only fragile but single, with one beginning and one end. It heightens the desire for your life to make sense as a whole, not just from certain angles. And with this comes renewed pressure for internal contradictions to be resolved, one way or another. For me, that meant sudden urgency around a question that had lingered unanswered for all of adulthood: how to reconcile my professional life with the fact that I am gay.

A YEAR LATER, it was my turn to fumble for a box, and now it was definitely a ring. We were on another New Year vacation (the days between Christmas and New Year’s are the nearest it gets to a quiet time in the mayor’s office), and I had lured him to Gate B5 at Chicago’s O’Hare Airport, the spot where he said he was killing time between herds of exchange students when he first noticed my profile on his phone and began chatting with me. I had worked out what kind of ring he wanted—a platinum band with a little square diamond in the middle—and made sure his parents and mine knew about my plans. All that remained was to ask him.

This won’t sound romantic to those who don’t know us, but I had selected the space behind the gate agent’s desk, a three-foot-wide zone against the window where you have something resembling privacy while looking out on the tarmac. In a way, O’Hare had brought us together. Plus, the halfway-secluded space in the midst of the busy concourse was symbolic for how our life together would be. “I can’t promise you an easy life or a simple one. And sometimes privacy for us will be like this, stealing away a quiet moment even with people all around us. It won’t always be elegant. But I promise it will always be an adventure, and I promise to love you forever.” I went ahead and got on one knee.

Through the tears, he said yes.

Then something happened that I did not see coming. Local press began reporting on rumors that the tapes contained evidence of officers using racist language to describe the former chief. (All of the five officers known to have been recorded were white.) The content of the tapes had not come up when I was talking with staff or with the chief about the issue. If true, this was explosive, and serious. The credibility and legitimacy of our police department depended heavily on the expectation that officers did their job with no racial animus. And since so many of the worst race-based abuses in modern American history happened at the hands of law enforcement, policing was the most sensitive part of the entire administration when it came to demonstrating that we acted without bias.

Infuriatingly, I had no way of finding out if this was actually true. The entire crisis was the result of the fact that the recordings were allegedly made in violation of the law. Under the Federal Wiretap Act, this meant that it could be a felony not just to make the recordings, but to reproduce and disclose them. Like everyone else in the community, I wanted to know what was on these recordings. But it was potentially illegal for me to find out, and it was not clear I could even ask, without fear of legal repercussions. As of this writing, I have not heard the recordings, and I still don’t know if I, and the public, ever will.

True hope for our city never lay in returning to some nostalgic prior state, some literal or figurative return of Studebaker. Rather, the first vision of the resurgent South Bend in which we now live was expressed all the way back in that bleak December of 1963 when the store owner Paul Gilbert defiantly told the assembly of alarmed fellow city leaders, “This is not Studebaker, Indiana. This is South Bend, Indiana.” At the time, it might have sounded like wishful thinking. No doubt many in his audience, knowing how dependent our city was on that industry, exchanged skeptical glances at one another, supposing that he was in denial.

But the real denial, and the more costly, was to persist in believing that South Bend could only thrive as an old-school, automaking company town dependent on a single, massive employer. I would encounter this thinking even a half century later in 2011 when I was running for mayor. I heard it as a refrain among those who said that what we needed was to land that one mythic giant factory, to lure “something big” here from somewhere else, and get some version of Studebaker taking root again. This was the impossible promise that held us back—and, seeing this promise go unkept, my generation grew up suspecting that our only hope was to get out.

Progress could begin only once the loss had been fully metabolized. Nothing is more human than to resist loss, which is why cynical politicians can get pretty far by offering up the fantasy that a loss can be reversed rather than overcome the hard way. This is the deepest lie of our recent national politics, the core falsehood encoded in “Make America Great Again.” Beneath the impossible promises—that coal alone will fuel our future, that a big wall can be built around our status quo, that climate change isn’t even real—is the deeper fantasy that time itself can be reversed, all losses restored, and thus no new ways of life required.

No comments:

Post a Comment