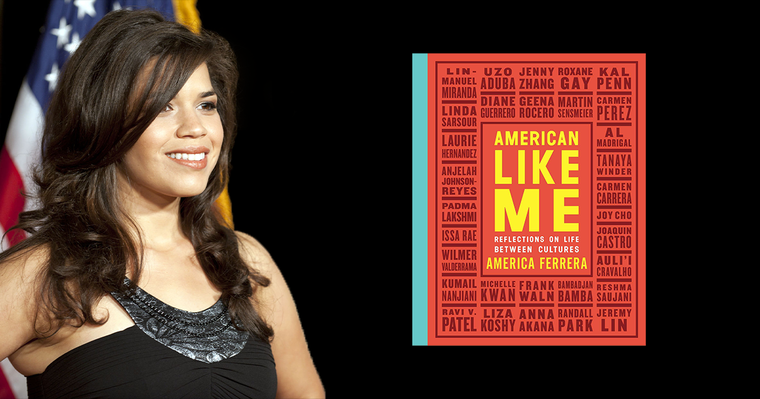

Here are a few excerpts from a book I recently read, "American Like M: Reflections on Life Between Cultures," by America Ferrera.

Here are a few excerpts from a book I recently read, "American Like M: Reflections on Life Between Cultures," by America Ferrera.“Actually, I like to go by my middle name, Georgina, so could you please make a note of it on the roster-paper-thingy? Thanks.” When he has the gall to ask me why, I say something like “It’s just easier,” instead of what I really want to say, which is “Because people like you make my name unbearably embarrassing! And another thing, I’m not actually named after the United States of America! I’m named after my mother, who was born and raised in Honduras. That’s in Central America, in case you’ve never heard of it, also part of the Americas. And if you must know, she was born on an obscure holiday called Día de Las Américas, which not even people in Honduras know that much about, but my grandfather was a librarian and knew weird shit like that. This is a holiday that celebrates all the Americas—South, Central, and North, not just the United States of. So, my name has nothing to do with amber waves of grain, purple mountains, the US flag, or your very narrow definition of the word. It’s my mother’s name and a word that also relates to other countries, like the one my parents come from. So please refrain from limiting the meaning of my name, erasing my family’s history, and making me the least popular kid in class all in one fell swoop. Just call me Georgina, please?” I don’t say any of this, to anyone. Ever. It would be impolite, or worse, unpatriotic. And as I said before, I love my country in the most unironic and earnest way anyone can love anything.

I know just how lucky I am to be an American because every time I complain about too much homework my mother reminds me that in Honduras I’d be working to help support the family, so I’d better thank my lucky stars that she sacrificed everything she had so that my malcriadaI self and my five siblings could one day have too much homework. It’s a perspective that has me embracing Little League baseball, the Fourth of July, and ABC’s TGIF lineup of wholesome American family comedies with more fervor than most. I feel more American than Balki Bartokomous, the Winslows, and the Tanners combined, and I believe that one day I will grow up to look like Aunt Becky from Full House and then Frank Sinatra will ask me to rerecord “I’ve Got You Under My Skin” as a duet with him because I know all the words better than my siblings.

So I let it slide when people respond to my name with “Wow, your parents must be very patriotic. Where are they ACTUALLY from?” This is a refrain I hear often and one that will take me a couple of decades to unpack for all its implications and assumptions. I learn to go along with the casting of my parents as the poor immigrants yearning to breathe free, who made it to the promised land and decided to name their American daughter after the soil that would fulfill all their dreams. After all, it is a beautiful and endearing tale. Only later do I learn to bristle and push back against this incomplete narrative. A narrative which manages to erase my parents’ history, true experience, and claim to the name America long before they had a US-born child. Never mind that they’d already had a US-born child before me and named her Jennifer. Which is both a much more American name than mine and one I would kill to have on the first day of every school year.

It is 1994, and California just voted in favor of Proposition 187—an initiative to deny undocumented immigrants and their children public services, including access to public education for kindergarten through university. There is fear inside the immigrant community that their children will be harassed and questioned in their schools.

I am in third grade and do not know or understand any of this. Nonetheless, my mother pulls me aside one day when she is dropping me off at school and says, “You are American. You were born in this country. If anyone asks you questions, you don’t need to feel ashamed or embarrassed. You’ve done nothing wrong.”

The first audition I ever went on, the casting director asked me if I could “try to sound more Latina.”

“Ummmm . . . do you want me to do it in Spanish?” I asked.

“No, no, do it in English, just sound like you’re a Latina,” she clarified.

“But I am Latina, soooo isn’t this what a Latina sounds like?” I asked.

“Okay, never mind, honey. Thanks for coming in, byeeee,” she said as she waved me toward the door. It took me far too long to understand she wanted me to speak in broken English. And instead of being sad that I didn’t get the part, I was angry that she thought sounding Latina meant not speaking English well.

Before they threw the dart that landed on Illinois, they were denied access to several other countries. The United States was the only nation that would have them. My father immediately began looking for a job as a mechanical engineer and was promptly told by a recruiter that he should Americanize his name and lose the accent. My dad, Mukund, became Mike. My mother, Mrudula, became Meena. And a few years later, when he was working in a factory and she was working at a cosmetics counter, Mike and Meena had me. And named me Reshma.

“Why didn’t you guys give me a normal name?!” I remember asking this for the first time around the age of ten. I was reading Sweet Valley High books and contemplating how easily they could have made me an Elizabeth or a Jessica. Because even though my parents’ name changes may have helped them get jobs, it didn’t stop our house from getting regularly egged and TP’d by the kids at school. As we attempted to cover the spray-painted words dot head go home off the side of our house, I couldn’t help but wonder if maybe they could change my name too.

I marveled at what it would feel like to wave your hand and transform everything. One day, Mukund was suddenly Mike. From that day forward his name was on a key chain. A person could simply authenticate himself as an American and enjoy the American-size horizon of possibilities that came with it. Why shouldn’t I blink my eyes and reopen them as a Rebecca?

(Reshma Saujani)

I had spent years assimilating as a child, and for the first time, I thought I knew why my parents named me Reshma.

Maybe they didn’t want me to blend in as much as I thought. They blended in so I wouldn’t have to. They paid the ultimate price for my authenticity. They gave up their community, their careers, their language, their own names. These were the steep taxes they paid to make a better life for me. Assimilating in the ways my parents did can invite accusations. Changing your name and hiding your accent could be seen as passive or fearful gestures. But my parents’ immigrant experience reveals the great reserves of bravery and pride they had in order to survive in a new country with no familiar community of support. I think my parents are the bravest people I know. They traded in their names for the freedom and privilege I experience every day. Because of them, I have the platform to be brave. They built the stage I stood on at the PRISM assembly. They laid the groundwork for a little girl named Reshma to grow up and become the first Indian-American woman to run for Congress.

They changed their names so I wouldn’t have to.

(Roxane Gay)

The older I get, the more I understand why my family loves the way they do. I understand what it took for my parents and their siblings to come to the United States. They had no money. They did not speak the language. They had no guarantee that the American dream would extend to them. All they had was each other. All they had was a fierce kind of love to see them through. When I consider what they sacrificed, what they went through as they made this country their own, and how they never let go of where they came from, it makes perfect sense that they would love without boundaries. They are people who have spent the whole of their lives crossing borders that were, often, unfriendly and unwilling to welcome them. They could not, I imagine, tolerate inhospitable borders within their own family, so they loved us in a wild, irrepressible, boundless way. They taught us to love that way in return, and so we do.

(Michelle Kwan )

I didn’t want to rise slowly in the rankings as he was advising. I wanted to be a shooting star—and the youngest in the senior level by many years. It was a huge risk, but once I made up my mind, I had to go for it. It was like my parents coming to America, carrying out what was maybe not the most ideal plan but definitely the right thing to do. My mom and dad have demonstrated time and again that you don’t have to plan perfect transitions in life. You don’t have to land flawlessly. You just have to take the leap.

(Uzo Aduba)

The full name she gave me is Uzoamaka, which of course no one could ever say correctly. I became fed up with teachers butchering the pronunciation and kids making fun of it, so one day, I approached her in the kitchen while she was cooking (which is where she is located in so many of my childhood memories). I proposed she start calling me Zoe instead.

“Why?” she said with such elegant disdain.

“Because no one can say Uzoamaka!” I said.

Without even looking up from the giant pot she was stirring, she replied, “If they can learn to say Tchaikovsky and Michelangelo and Dostoevsky, then they can learn to say Uzoamaka.”

No comments:

Post a Comment