Too Short for a Blog Post, Too Long for a Tweet 190

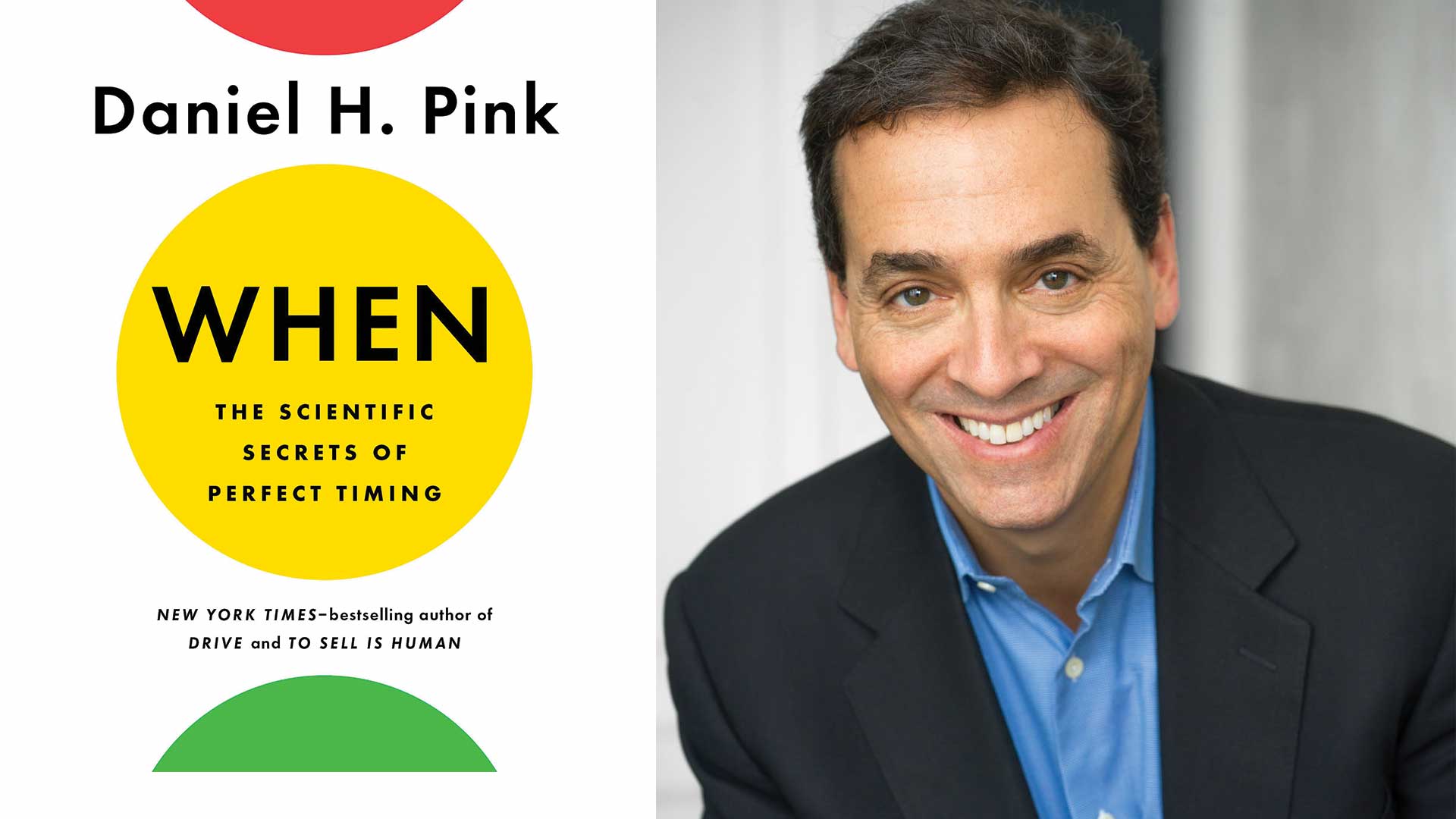

Here are a few excerpts from a book I recently read, "When: The Scientific Secrets of Perfect Timing," by Daniel H. Pink.

Here are a few excerpts from a book I recently read, "When: The Scientific Secrets of Perfect Timing," by Daniel H. Pink.

This is a book about timing. We all know that timing is

everything. Trouble is, we don’t know much about timing itself. Our

lives present a never-ending stream of “when” decisions—when to change

careers, deliver bad news, schedule a class, end a marriage, go for a

run, or get serious about a project or a person. But most of these

decisions emanate from a steamy bog of intuition and guesswork. Timing,

we believe, is an art.

I will

show that timing is really a science—an emerging body of multifaceted,

multidisciplinary research that offers fresh insights into the human

condition and useful guidance on working smarter and living better.

Visit any bookstore or library, and you will see a shelf (or twelve)

stacked with books about how to do various things—from win friends and

influence people to speak Tagalog in a month. The output is so massive

that these volumes require their own category: how-to. Think of this

book as a new genre altogether—a when-to book.

When an economist studied the Wake County, North

Carolina, school system, he found that “a 1 hour delay in start time

increases standardized test scores on both math and reading tests by

three percentile points,” with the strongest effects on the weakest

students. But being an economist, he also calculated the cost-benefit

ratio of changing the schedule and concluded that later start times

delivered more bang for the educational buck than almost any other

initiative available to policy makers, a view echoed by a Brookings

Institution analysis.

Yet the

pleas of the nation’s pediatricians and its top public-health officials,

as well as the experiences of schools that have challenged the status

quo, have been largely ignored. Today, fewer than one in five U.S.

middle schools and high schools follow the AAP’s recommendation to begin

school after 8:30 a.m. The average start time for American adolescents

remains 8:03 a.m., which means huge numbers of schools start in the 7

a.m. hour.

Why the

resistance? A key reason is that starting later is inconvenient for

adults. Administrators must reconfigure bus schedules. Parents might not

be able to drop off their kids on the way to work. Teachers must stay

later in the afternoon. Coaches might have less time for sports

practices.

But beneath

those excuses is a deeper, and equally troubling, explanation. We simply

don’t take issues of when as seriously as we take questions of what.

Imagine if schools suffered the same problems wrought by early start

times—stunted learning and worsening health—but the cause was an

airborne virus that was infecting classrooms. Parents would march to the

schoolhouse to demand action and quarantine their children at home

until the problem was solved. Every school district would snap into

action. Now imagine if we could eradicate that virus and protect all

those students with an already-known, reasonably priced, simply

administered vaccine. The change would have already happened. Four out

of five American school districts—more than 11,000—wouldn’t be ignoring

the evidence and manufacturing excuses. Doing so would be morally

repellent and politically untenable. Parents, teachers, and entire

communities wouldn’t stand for it.

The

school start time issue isn’t new. But because it’s a when problem

rather than a what problem such as viruses or terrorism, too many people

find it easy to dismiss.

Call it the “uh-oh effect.”

When

we reach a midpoint, sometimes we slump, but other times we jump. A

mental siren alerts us that we’ve squandered half of our time. That

injects a healthy dose of stress—Uh-oh, we’re running out of time!—that

revives our motivation and reshapes our strategy.

What

Adhav does is fundamentally different from delivering a Domino’s pizza.

He sees one member of a family early in the morning, then another later

in the day. He helps the former nourish the latter and the latter

appreciate the former. Adhav is the connective tissue that keeps

families together. That pizza delivery guy might be efficient, but his

work is not transcendent. Adhav, though, is efficient because his work

is transcendent.

He

synchs first to the boss—that 10:51 a.m. train from the Vile Parle

station. He synchs next to the tribe—his fellow white-hatted walas who

speak the same language and know the cryptic code. But he ultimately

synchs to something more sublime—the heart—by doing difficult,

physically demanding work that nourishes people and bonds families.

I used to believe that timing was everything. Now I believe that everything is timing.

Comments