Too Short for a Blog Post, Too Long for a Tweet 186

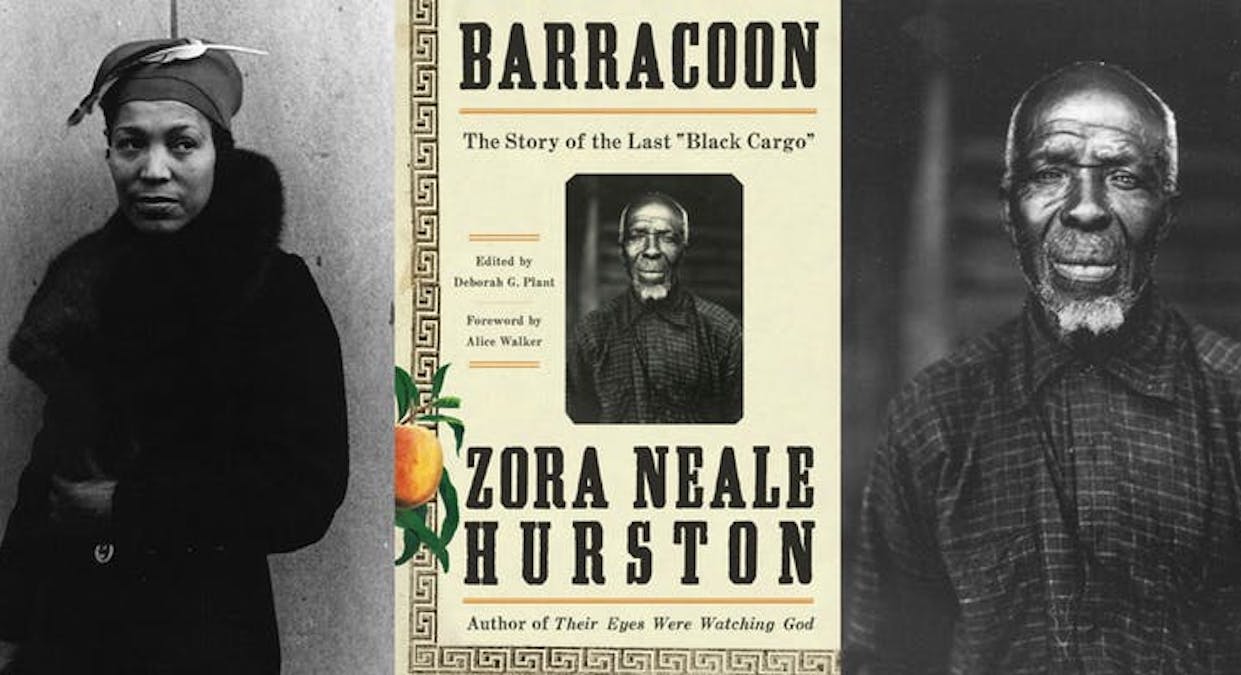

Here is an excerpt from a book I recently read, "Barracoon: The Story of the Last 'Black Cargo,'" by Zora Neale Hurston.

Here is an excerpt from a book I recently read, "Barracoon: The Story of the Last 'Black Cargo,'" by Zora Neale Hurston.Hurston’s manuscript is an invaluable historical document, as Diouf points out, and an extraordinary literary achievement as well, despite the fact that it found no takers during her lifetime. In it, Zora Neale Hurston found a way to produce a written text that maintains the orality of the spoken word. And she did so without imposing herself in the narrative, creating what some scholars classify as orature. Contrary to the literary biographer Robert Hemenway’s dismissal of Barracoon as Hurston’s re-creation of Kossola’s experience, the scholar Lynda Hill writes that “through a deliberate act of suppression, she resists presenting her own point of view in a natural, or naturalistic, way and allows Kossula ‘to tell his story in his own way.’”

Zora

Neale Hurston was not only committed to collecting artifacts of African

American folk culture, she was also adamant about their authentic

presentation. Even as she rejected the objective-observer stance of

Western scientific inquiry for a participant-observer stance, Hurston

still incorporated standard features of the ethnographic and

folklore-collecting processes within her methodology. Adopting the

participant-observer stance is what allowed her to collect folklore

“like a new broom.” As Hill points out, Hurston was simultaneously

working and learning, which meant, ultimately, that she was not just

mirroring her mentors, but coming into her own.

Embedded

in the narrative of Barracoon are those aspects of ethnography and

folklore collecting that reveal Hurston’s methodology and authenticate

Kossola’s story as his own, rather than as a fiction of Hurston’s

imagination. The story, in the main, is told from Kossola’s first-person

point of view. Hurston transcribes Kossola’s story, using his

vernacular diction, spelling his words as she hears them pronounced.

Sentences follow his syntactical rhythms and maintain his idiomatic

expressions and repetitive phrases. Hurston’s methods respect Kossola’s

own storytelling sensibility; it is one that is “rooted ‘in African

soil.’” “It would be hard to make the case that she entirely invented

Kossula’s language and, consequently, his emerging persona,” comments

Hill. And it would be an equally hard case to make that she created

the life events chronicled in Kossola’s story.

Comments