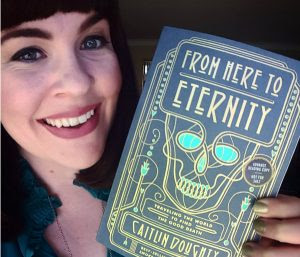

Here are a few excerpts from a book I recently read, "From Here to Eternity: Traveling the World to Find the Good Death," by Caitlin Doughty:

Here are a few excerpts from a book I recently read, "From Here to Eternity: Traveling the World to Find the Good Death," by Caitlin Doughty:In America, where I live, death has been big business since the turn of the twentieth century. A century has proven the perfect amount of time for its citizens to forget what funerals once were: family- and community-run affairs. In the nineteenth century no one would have questioned Josephine’s daughter preparing her mother’s body—it would have seemed strange if she didn’t. No one would have questioned a wife washing and dressing the body of her husband or a father carrying his son to the grave in a homemade coffin. In an impressively short time, America’s funeral industry has become more expensive, more corporate, and more bureaucratic than any other funeral industry on Earth. If we can be called best at anything, it would be at keeping our grieving families separated from their dead.

One of the chief questions in my work has always been why my own culture is so squeamish around death. Why do we refuse to have these conversations, asking our family and friends what they want done with their body when they die? Our avoidance is self-defeating. By dodging the talk about our inevitable end, we put both our pocketbooks and our ability to mourn at risk.

I believed that if I could witness firsthand how death is handled in other cultures, I might be able to demonstrate that there is no one prescribed way to “do” or understand death. In the last several years I have traveled to observe death rituals as they are practiced around the world—in Australia, England, Germany, Spain, Italy, Indonesia, Mexico, Bolivia, Japan, and throughout the U.S. There is much to learn from the cremation pyres of India and the whimsical coffins of Ghana, but the places I chose to visit have tales equally spectacular and less often told. I hope that what I found might help us reclaim meaning and tradition in our own communities. Such reclamation is important to me as a funeral home owner, but more so as a daughter and a friend.

Any answered prayer can be viewed as a coincidence or not. I wasn’t in La Paz to determine whether the ñatitas had true magical powers. I was more interested in women like Doña Ely and Doña Ana, and the hundreds of other people at the Fiesta, who were using their comfort with death to seize direct access to the divine from the hands of the male leaders of the Catholic Church. As Paul bluntly put it, the skulls are “technology for disadvantaged people.” No problem—whether love, family, or school—is too small for a ñatita, and no person is left behind.

Death avoidance is not an individual failing; it’s a cultural one. Facing death is not for the faint-hearted. It is far too challenging to expect that each citizen will do so on his or her own. Death acceptance is the responsibility of all death professionals—funeral directors, cemetery managers, hospital workers. It is the responsibility of those who have been tasked with creating physical and emotional environments where safe, open interaction with death and dead bodies is possible.

Nine years ago, when I began working with the dead, I heard other practitioners speak about holding the space for the dying person and their family. With my secular bias, “holding the space” sounded like saccharine hippie lingo.

This judgment was wrong. Holding the space is crucial, and exactly what we are missing. To hold the space is to create a ring of safety around the family and friends of the dead, providing a place where they can grieve openly and honestly, without fear of being judged.

No comments:

Post a Comment