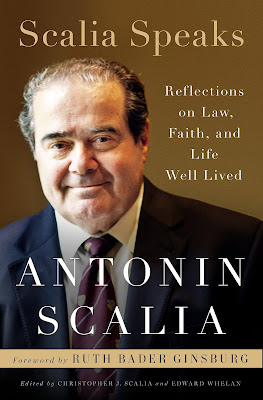

Here are a few excerpts from a book I recently read, "Scalia Speaks: Reflections on Law, Faith, and Life Well Lived," by Antonin Scalia.

Here are a few excerpts from a book I recently read, "Scalia Speaks: Reflections on Law, Faith, and Life Well Lived," by Antonin Scalia.

One’s

work is not to be taken lightly. Not only because it is a necessary

means of putting bread on the table, but because it is perhaps the

single most influential factor (apart from your own free will) in

determining what kind of people you will be. There is a profound

spiritual connection between a human being and his or her work. What we

do for a living is at once and the same time an expression of our

identity, and a formation of it. It is less true that we are what we eat

than that we are what we do to eat.

Lawyers

really have no more interest than anyone else—and no more expertise

than anyone else—in what the substance of our laws should be. If you

want to know whether deregulation is good or bad, ask an economist. If

you want to know whether indeterminate prison sentences are good or bad,

ask a criminologist or penologist. What lawyers are good at, what

lawyers are for, is implementing these decisions in a manner, through a

process, that is fair and reasonable.

I

fear that this characteristic of ours, which is perhaps our most

distinctive and profound characteristic, will never be understood by the

layman. It is the source of the most common criticism of lawyers: that

we can argue both sides of a case. But of course we can—because except

to the extent that a client’s interest may be involved, we as lawyers

have no interest in a particular outcome, but only in assuring that the

outcome be fairly and intelligently arrived at and clearly and precisely

expressed!

Movement

is not necessarily progress. More important than your obligation to

follow your conscience—or at least prior to it—is your obligation to

form your conscience correctly.

The

reason, of course, is that a bill of rights has value only if the other

part of the constitution—the part that really “constitutes” the organs

of government—establishes a structure that is likely to preserve,

against the ineradicable human lust for power, the liberties that the

bill of rights expresses. If the people value those liberties, the

proper constitutional structure will likely result in their preservation

even in the absence of a bill of rights; and where that structure does

not exist, the mere recitation of the liberties will certainly not

preserve them. So while it is entirely appropriate for us Americans to

celebrate our wonderful Bill of Rights, we realize (or should realize)

that it represents the fruit, and not the roots, of our constitutional

tree. The rights it expresses are the reasons that the other provisions

exist. But it is those other humdrum provisions—the structural,

mechanistic portions of the Constitution that pit, in James Madison’s

words, “ambition against ambition,” and make it impossible for any

element of government to obtain unchecked power—that convert the Bill of

Rights from a paper assurance to a living guarantee. A crowd is much

more likely to form behind a banner that reads “Freedom of Speech or

Death” than behind one that says “Bicameralism or Fight”; but the latter

in fact goes much more to the root of the matter.

The

consequences of this phenomenon in the United States have not been

good, either for judging or for democracy. As for judging: to get

confirmed to a federal court in the United States, one must be nominated

by the president and confirmed by the Senate. This used to be, for the

most part, a fairly routine process. But it has become a major

battleground for the political parties and the interest groups, a major

issue in every presidential campaign. When an individual is nominated

for a federal judgeship, few Americans care whether the nominee will

approach each case with an independence of mind, or a reasoned process

of decision-making. Americans care instead about results. Will the

nominee, for example, uphold the right to abortion on demand? This trend

is an unfortunate one, but it is entirely understandable. Once the

vocation of a judge is conceived of as the vocation of the common-law

judge, why shouldn’t Americans care what that judge thinks about the

moral issues of the day? The result is a nomination process that

politicizes the judiciary.

The

judge as legislator has also not been good for democracy. When the

vocation of a judge is reduced to simply selecting the best rule,

remarkable power is placed in the hands of a few persons who are barely

accountable for their decisions. In my country, most judges are given

life tenure, and it is almost impossible to get a judge impeached. This

was originally designed to give judges some insulation from the public

indignation that often accompanies unpopular decisions. But when the

vocation of a judge is more akin to that of a lawmaker, such insulation

seems remarkably inapt. Moreover, there is no reason to suspect that the

justices on my court, for example, are particularly good

representatives of the views that a majority of Americans hold. We all

live in Washington, D.C., for goodness’ sake—we are totally out of touch

with America! And we are all lawyers. Since when would a majority of

Americans think that a group of nine lawyers from elite law schools

should be entrusted with deciding the “best rules” for all of our

countrymen to live by?

Another

criticism of originalism—perhaps the most common one—is that it

petrifies the law. Thus, the approach set up in opposition to

originalism is sometimes called the approach of the “living

Constitution”—a constitution that evolves as the needs of society

require. Seems very attractive. But if you think that the proponents of a

living Constitution are trying to bring you flexibility and the power

to change, you should think again. A constitution is designed to provide

not flexibility but rigidity—and that is precisely what the proponents

of a living Constitution use it for. The originalists’ Constitution

permits expansive change when the people desire it. Do you want the

death penalty? Elect those who will impose it. Do you abhor the death

penalty? Elect those who will abolish it. And you can change your mind.

If you find that the murder rate goes up after the abolition of the

death penalty, elect those who will reinstitute it. If, however, the

living constitutionalists have their way and declare the death penalty

unconstitutional, the people’s power to choose is eliminated. No death

penalty, period.

That is

what has happened, of course, with abortion. The Constitution says

nothing about the subject. It neither forbids (as the pro-choice people

claim) nor requires (as the pro-life people claim) restrictions upon it.

For two centuries, laws in every state prohibited it, but now, under a

living-Constitution theory, it cannot be prohibited. No use trying to

persuade your fellow citizens one way or the other about the subject. It

has been taken off the democratic stage. And that is, of course,

precisely what those who argued for Roe v. Wade desired to achieve. So

don’t love the living Constitution because it will bring you flexibility

and choice; it will bring you rigidity, which is precisely what it is

designed for.

The

Europeans, and most other countries of the world, look at our system

with something approaching disbelief. One House passes a bill, and the

other House, which may be controlled by the other party, disapproves it.

Or they both approve it, but the president exercises a veto. This is,

they solemnly pronounce, a recipe for gridlock. It is indeed, and our

Framers would say hooray. It is precisely that dispersal of power that

they believed would be the primary bulwark of minorities against the

tyranny of the majority. It does not take much to stop legislation that

grievously injures a determined minority. It is easy to throw a monkey

wrench into the works. By and large, only legislation with broad support

will emerge from the complex system.

There

is of course a great irony in this new practice of selecting justices

on the basis of what kind of Constitution the People desire. The whole

purpose of the Bill of Rights is to protect individuals against the

wishes of the people; and in enforcing the restrictions contained in

those provisions, the courts act in a decidedly anti-democratic

capacity. They tell the people that they cannot do what they would like

to do. Thus, to turn the interpretation of the Constitution over to

majority opinion is to place the Bill of Rights in the hand of precisely

the entity it was meant to protect against.

No comments:

Post a Comment