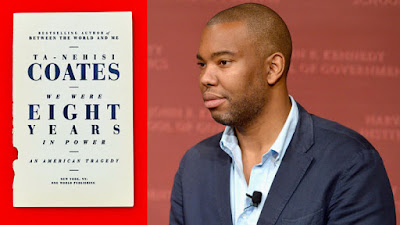

Here are a few excerpts from a book I recently read, "We Were Eight Years in Power: An American Tragedy," by Ta-Nehisi Coates:

Here are a few excerpts from a book I recently read, "We Were Eight Years in Power: An American Tragedy," by Ta-Nehisi Coates:

Toward the end of the Civil War, having witnessed the

effectiveness of the Union’s “colored troops,” a flailing Confederacy

began considering an attempt to recruit blacks into its army. But in the

nineteenth century, the idea of the soldier was heavily entwined with

the notion of masculinity and citizenship. How could an army constituted

to defend slavery, with all of its assumptions about black inferiority,

turn around and declare that blacks were worthy of being invited into

Confederate ranks? As it happened, they could not. “The day you make a

soldier of them is the beginning of the end of our revolution,” observed

Georgia politician Howell Cobb. “And if slaves seem good soldiers, then

our whole theory of slavery is wrong.” There could be no win for white

supremacy here. If blacks proved to be the cowards that “the whole

theory of slavery” painted them as, the battle would literally be lost.

But much worse, should they fight effectively—and prove themselves

capable of “good Negro government”—then the larger war could never be

won.

The central thread of

this book is eight articles written during the eight years of the first

black presidency—a period of Good Negro Government. Obama was elected

amid widespread panic and, in his eight years, emerged as a caretaker

and measured architect. He established the framework of a national

healthcare system from a conservative model. He prevented an economic

collapse and neglected to prosecute those largely responsible for that

collapse. He ended state-sanctioned torture but continued the

generational war in the Middle East. His family—the charming and

beautiful wife, the lovely daughters, the dogs—seemed pulled from the

Brooks Brothers catalogue. He was not a revolutionary. He steered clear

of major scandal, corruption, and bribery. He was deliberate to a fault,

saw himself as the keeper of his country’s sacred legacy, and if he was

bothered by his country’s sins, he ultimately believed it to be a force

for good in the world. In short, Obama, his family, and his

administration were a walking advertisement for the ease with which

black people could be fully integrated into the unthreatening mainstream

of American culture, politics, and myth.

And that was always the problem.

One

strain of African American thought holds that it is a violent black

recklessness—the black gangster, the black rioter—that strikes the

ultimate terror in white America. Perhaps it does, in the most

individual sense. But in the collective sense, what this country really

fears is black respectability, Good Negro Government. It applauds, even

celebrates, Good Negro Government in the unthreatening abstract—The

Cosby Show, for instance. But when it becomes clear that Good Negro

Government might, in any way, empower actual Negroes over actual whites,

then the fear sets in, the affirmative-action charges begin, and

birtherism emerges. And this is because, at its core, those American

myths have never been colorless. They cannot be extricated from the

“whole theory of slavery,” which holds that an entire class of people

carry peonage in their blood. That peon class provided the foundation on

which all those myths and conceptions were built. And as much as we can

theoretically imagine a seamless black integration into the American

myth, the white part of this country remembers the myth as it was

conceived.

I think the

old fear of Good Negro Government has much explanatory power for what

might seem a shocking turn—the election of Donald Trump. It has been

said that the first black presidency was mostly “symbolic,” a dismissal

that deeply underestimates the power of symbols. Symbols don’t just

represent reality but can become tools to change it. The symbolic power

of Barack Obama’s presidency—that whiteness was no longer strong enough

to prevent peons from taking up residence in the castle—assaulted the

most deeply rooted notions of white supremacy and instilled fear in its

adherents and beneficiaries. And it was that fear that gave the symbols

Donald Trump deployed—the symbols of racism—enough potency to make him

president, and thus put him in position to injure the world.

There

is a basic assumption in this country, one black people are not immune

to, which holds that if blacks comport themselves in a way that accords

with middle-class values, if they are polite, educated, and virtuous,

then all the fruits of America will be open to them. In its most vulgar

form, this theory of personal Good Negro Government denies the existence

of racism and white supremacy as meaningful forces in American life. In

its more nuanced and reputable form, the theory pitches itself as an

equal complement to anti-racism. But the argument made in much of this

book is that Good Negro Government—personal and political—often augments

the very white supremacy it seeks to combat.

In

those days I imagined racism as a tumor that could be isolated and

removed from the body of America, not as a pervasive system both native

and essential to that body. From that perspective, it seemed possible

that the success of one man really could alter history, or even end it.

I

also saw that those charged with analyzing the import of Obama’s

blackness were, in the main, working off an old script. Obama was dubbed

“the new Tiger Woods of American politics,” as a man who wasn’t

“exactly black.” I understood the point—Obama was not “black” as these

writers understood “black.” It wasn’t just that he wasn’t a drug dealer,

like most black men on the news, but that he did not hail from an inner

city, he was not raised on chitterlings, his mother had not washed

white people’s floors. But this confusion was a reduction of racism’s

true breadth, premised on the need to fix black people in one corner of

the universe so that white people may be secure in all the rest of it.

So to understand Obama, analysts needed to give him a superpower that

explained how this self-described black man escaped his assigned corner.

That power was his mixed ancestry.

That

war was inaugurated not reluctantly, but lustily, by men who believed

property in humans to be the cornerstone of civilization, to be an edict

of God, and so delivered their own children to his maw. And when that

war was done, the now-defeated God lived on, honored through the human

sacrifice of lynching and racist pogroms.

The consequences of 250 years of enslavement, of war

upon black families and black people, were profound. Like homeownership

today, slave ownership was aspirational, attracting not just those who

owned slaves but those who wished to. Much as homeowners today might

discuss the addition of a patio or the painting of a living room,

slaveholders traded tips on the best methods for breeding workers,

exacting labor, and doling out punishment. Just as a homeowner today

might subscribe to a magazine like This Old House, slaveholders had

journals such as De Bow’s Review, which recommended the best practices

for wringing profits from slaves. By the dawn of the Civil War, the

enslavement of black America was thought to be so foundational to the

country that those who sought to end it were branded heretics worthy of

death. Imagine what would happen if a president today came out in favor

of taking all American homes from their owners: The reaction might well

be violent.

The

omnibus programs passed under the Social Security Act in 1935 were

crafted in such a way as to protect the southern way of life. Old-age

insurance (Social Security proper) and unemployment insurance excluded

farmworkers and domestics—jobs heavily occupied by blacks. When

President Roosevelt signed Social Security into law in 1935, 65 percent

of African Americans nationally and between 70 and 80 percent in the

South were ineligible. The NAACP protested, calling the new American

safety net “a sieve with holes just big enough for the majority of

Negroes to fall through.”

The

oft-celebrated GI Bill similarly failed black Americans, by mirroring

the broader country’s insistence on a racist housing policy. Though

ostensibly color-blind, Title III of the bill, which aimed to give

veterans access to low-interest home loans, left black veterans to

tangle with white officials at their local Veterans Administration as

well as with the same banks that had, for years, refused to grant

mortgages to blacks. The historian Kathleen J. Frydl observes in her

2009 book The GI Bill that so many blacks were disqualified from

receiving Title III benefits “that it is more accurate simply to say

that blacks could not use this particular title.”

We

invoke the words of Jefferson and Lincoln because they say something

about our legacy and our traditions. We do this because we recognize our

links to the past—at least when they flatter us. But black history does

not flatter American democracy; it chastens it. The popular mocking of

reparations as a harebrained scheme authored by wild-eyed lefties and

intellectually unserious black nationalists is fear masquerading as

laughter. Black nationalists have always perceived something

unmentionable about America that integrationists dare not

acknowledge—that white supremacy is not merely the work of hotheaded

demagogues, or a matter of false consciousness, but a force so

fundamental to America that it is difficult to imagine the country

without it.

And so we

must imagine a new country. Reparations—by which I mean the full

acceptance of our collective biography and its consequences—is the price

we must pay to see ourselves squarely. The recovering alcoholic may

well have to live with his illness for the rest of his life. But at

least he is not living a drunken lie. Reparations beckon us to reject

the intoxication of hubris and see America as it is—the work of fallible

humans.

Antebellum

Virginia had seventy-three crimes that could garner the death penalty

for slaves—and only one for whites. The end of enslavement posed an

existential crisis for white supremacy, because an open labor market

meant blacks competing with whites for jobs and resources, and—most

frightening—black men competing for the attention of white women.

Postbellum Alabama solved this problem by manufacturing criminals.

Blacks who could not find work were labeled vagrants and sent to jail,

where they were leased as labor to the very people who had once enslaved

them.

But

the argument that America’s original sin was not deep-seated white

supremacy but rather the exploitation of white labor by white

capitalists—“white slavery”—proved durable. Indeed, the panic of white

slavery lives on in our politics today. Black workers suffer—if it can

be called that—because it was and is our lot. But when white workers

suffer, something in nature has gone awry. And so an opioid epidemic is

greeted with a call for treatment and sympathy, as all epidemics should

be, while a crack epidemic is greeted with a call for mandatory minimums

and scorn. Op-ed columns and articles are devoted to the sympathetic

plight of working class whites when their life expectancy approaches

levels that, for blacks, society simply accepts as normal. White slavery

is sin. Ni**er slavery is natural. This dynamic serves a very real

purpose—the consistent awarding of grievance and moral high ground to

that class of workers who, by the bonds of whiteness, stands closest to

America’s master class.

No comments:

Post a Comment