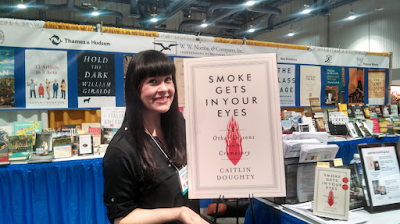

Here's an excerpt from a book I recently read, "Smoke Gets in Your Eyes: And Other Lessons from the Crematory," by Caitlin Doughty:

Here's an excerpt from a book I recently read, "Smoke Gets in Your Eyes: And Other Lessons from the Crematory," by Caitlin Doughty:Every culture has death values. These values are transmitted in the form of stories and myths, told to children starting before they are old enough to form memories. The beliefs children grow up with give them a framework to make sense of and take control of their lives. This need for meaning is why some believe in an intricate system of potential afterlives, others believe sacrificing a certain animal on a certain day leads to healthy crops, and still others believe the world will end when a ship constructed with the untrimmed nails of the dead arrives carrying a corpse army to do battle with the gods at the end of days. (Norse mythology will always be the most metal, sorry.)

But

there is something deeply unsettling—or deeply thrilling, depending on

how you view it—about what is happening to our death values. There has

never been a time in the history of the world when a culture has broken

so completely with traditional methods of body disposition and beliefs

surrounding mortality. There have been times when humans were driven to

break tradition by necessity—for example, deaths on a foreign

battlefield. But for the most part, when a person dies, they are

disposed of like their mother and father were, and like their mothers

and fathers were. Hindus were cremated, elite Egyptians entombed with

their organs in jars, Viking warriors buried in ships. And now, the

cultural norm is that Americans are either embalmed and buried, or

cremated. But culture no longer dictates that we must do those things,

out of belief or obligation.

Historically,

death rituals have, without question, been tied to religious beliefs.

But our world is becoming increasingly secular. The fastest-growing

religion in America is “no religion”—a group that comprises almost 20

percent of the population in the United States. Even those who identify

as having strong religious beliefs often feel their once-strong death

rituals have been commoditized and hold less meaning for them. At a time

like this, there is no limit to our creativity in creating rituals

relevant to our modern lives. The freedom is exciting, but it is also a

burden. We cannot possibly live without a relationship to our mortality,

and developing secular methods for addressing death will become more

critical as each year passes.

No comments:

Post a Comment