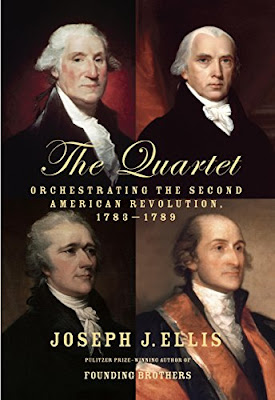

Here's three excerpts from a book I recently read, "The Quartet: Orchestrating the Second American Revolution, 1783-1789," by Joseph Ellis:

Here's three excerpts from a book I recently read, "The Quartet: Orchestrating the Second American Revolution, 1783-1789," by Joseph Ellis:Lincoln began as follows: “Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this Continent a new Nation.” No, not really. In 1776 thirteen American colonies declared themselves independent states that came together temporarily to win the war, then would go their separate ways. The government they created in 1781, called the Articles of Confederation, was not really much of a government at all and was never intended to be. It was, instead, what one historian has called a “Peace Pact” among sovereign states that regarded themselves as mini-nations of their own, that came together voluntarily for mutual security in a domestic version of a League of Nations.

And once you started thinking along these lines, there were reasons as self-evident as Jefferson’s famous truths why no such thing as a coherent American nation could possibly have emerged after independence was won. Politically, a state-based framework followed naturally from the arguments that the colonies had been hurling at the British ministry for over a decade, which denied Parliament’s right to tax them because that authority resided within the respective colonial legislatures, which represented their constituents in a more direct and proximate fashion than those distant members of Parliament could ever do. The resolution declaring independence, approved on July 2, 1776, clearly states that the former colonies were leaving the British Empire not as a single collective but rather as “Free and Independent States.”

Distance also made a huge difference. The vast majority of Americans were born, lived out their lives, and died within a thirty-mile geographic radius. It took three weeks for a letter to get from Boston to Philadelphia. Political horizons and allegiances, therefore, were limited—obviously no such things as radios, cell phones, or the Internet existed to solve the distance problem—so the ideal political unit was the town or county government, where representatives could be trusted to defend your interests because they shared them as your neighbors.

Indeed, it was presumed that any faraway national government would represent a domestic version of Parliament, too removed from the interests and experiences of the American citizenry to be trusted. And distrusting such distant sources of political power had become a core ideological impulse of the movement for independence, often assuming quasi-paranoid hostility toward any projection of power from London and Whitehall, which was described as inherently arbitrary, imperious, and corrupt. And so creating a national government was the last thing on the minds of American revolutionaries, since such a distant source of political power embodied all the tyrannical tendencies that patriotic Americans believed they were rebelling against.

In 1863 Lincoln had some compelling reasons for bending the arc of American history in a national direction, since he was then waging a civil war on behalf of a union that he claimed predated the existence of the states. This was a fundamental distortion of how history happened, though we may wish to forgive Lincoln, since it was the only way for him to claim the political authority to end slavery.

Truth be known, nationhood was never a goal of the war for independence, and all the political institutions necessary for a viable American nation-state were thoroughly stigmatized in the most heartfelt convictions of revolutionary ideology. The only thing holding the American colonies together until 1776 was their membership in the British Empire. The only thing holding them together after 1776 was their common resolve to leave that empire. Once the war was won, that cord was cut, and the states began to float into their own at best regional orbits. Any historically informed prophet who was straddling that postwar moment could have safely predicted that North America was destined to become a western version of Europe, a constellation of rival political camps and countries, all jockeying for primacy. That, at least, was the clear direction in which American history was headed.

***

The multiple compromises reached in the Constitutional Convention over where to locate sovereignty accurately reflected the deep divisions in the American populace at large. There was a strong consensus that the state-based system under the Articles had proven ineffectual, but an equally strong apprehension about the political danger posed by any national government that rode roughshod over local, state, and regional interests, which were the familiar spaces where the vast majority of American lived out their lives. As Madison now realized, the Constitution created a federal structure that moved the American republic toward nationhood while retaining an abiding place for local and state allegiances. In that sense, it was a second American Revolution that took the form of an American Evolution, which allowed the citizenry to adapt gradually to its national implications.

In

the long run—and this was probably Madison’s most creative insight—the

multiple ambiguities embedded in the Constitution made it an inherently

“living” document. For it was designed not to offer clear answers to the

sovereignty question (or, for that matter, to the scope of executive or

judicial authority) but instead to provide a political arena in which

arguments about those contested issues could continue in a deliberative

fashion. The Constitution was intended less to resolve arguments than to

make argument itself the solution. For judicial devotees of

“originalism” or “original intent,” this should be a disarming insight,

since it made the Constitution the foundation for an ever-shifting

political dialogue that, like history itself, was an argument without

end. Madison’s “original intention” was to make all “original

intentions” infinitely negotiable in the future.

***

Finally,

under the rubric of his fourth proposed amendment, Madison wrote the

following words: “The right of the people to keep and bear arms shall

not be infringed; a well armed, and well regulated militia being the

best security of a free country; but no person religiously scrupulous of

bearing arms, shall be compelled to render military service in person.”

This eventually, after some editing in the Senate, became the Second

Amendment in the Bill of Rights, and its meaning has provoked more

controversy in our own time than it did in 1789.

No comments:

Post a Comment